What Will We Make? Using Process Art to Spark Preschoolers’ Development

You are here

Most mornings, the 4- and 5-year-olds in Room 21 at Frankfurt International School in Germany enter their classroom to tables set with various art materials. At one, drawing papers atop placemats are surrounded by trays of watercolors, varying sizes of paint brushes, black permanent markers, and pots of water. A rectangular table stands in front of a shelf with clear containers holding collections of cardboard boxes, cylinders, colored scrap paper, glue, and wire. On yet another table, plasticine cubes of various colors await with old jam jars filled with wire, pipe cleaners, and beads.

In the center of the room is a shelf housing a collection of loose parts. Groups of old buttons, ribbons, seashells, bottle caps, and acorns sorted by color sit in repurposed plastic fruit trays. On the floor is an eclectic collection of red items surrounded by placemats inviting children to create collages.

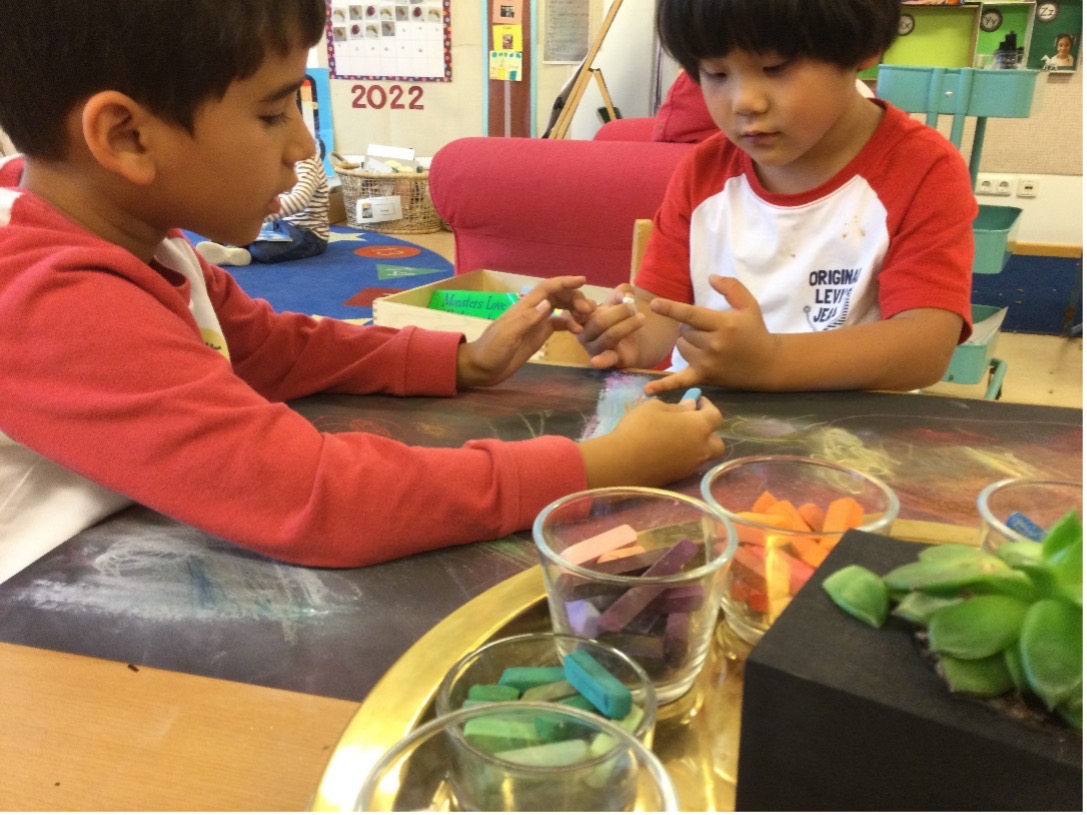

As the children enter, they choose different parts of the room to explore. Moojin and Ray settle at the plasticine table. They work across from each other, quietly and independently at first, rolling the plasticine into long skinny snakes and fat balls, stomping and smooshing in earnest. Eventually, a sense of purpose emerges in their kneading, pinching, and forming as their ideas begin to take shape.

Art experiences in preschool typically follow one of two approaches, both of which have value for young children. Product-focused art usually asks children to follow teachers’ directions or mimic samples to recreate a predetermined work. Teachers can use it to support fine motor and executive function skills. Process art—the focus of this article—is a choice-driven, open-ended activity in which teachers offer minimal guidance or scaffolding. By intentionally providing an array of artistic materials, then offering children the time and space to engage freely with them, teachers convey that there are many possibilities, that they view children as competent and capable of exploring and creating, and that they value children’s ideas and expressions. Process art can support children’s development in a variety of content areas and developmental domains. This article shares ways in which it can help children grow in their expressive language, nurture social and emotional development, and encourage thinking skills.

Process Art as a Means of Expression

Young learners are not always capable of telling or showing us what is on their minds. Art offers another way for them to express ideas and experiences, and it can strengthen their developing oral and written communication skills. This is particularly true for English language learners: in an unfamiliar world where they may be feeling lost and confused, process art can give them some control and agency.

Moojin, for example, was new to English. He also struggled with fine motor skills and typically avoided table-top, mark-making, and paper-and-pencil activities. But the plasticine helped him strengthen his fine motor skills. It also offered him a means of creating something beautiful that he could proudly share with his peers. Engaging with the plasticine gave Moojin time to process his thoughts and ideas. This, in turn, helped build his English vocabulary and other expressive language skills.

Teachers can encourage children to talk about their work in the language they feel most comfortable. They can record children’s stories and share these with families. They can also invite a family member to translate a child’s story, which will give insight into that child’s interests, help form a family connection, and enable teachers to provide English vocabulary when revisiting the child’s work.

Process Art’s Social and Emotional Benefits

Moojin begins to make an elephant-like creature from the plasticine. He struggles to keep its trunk up. Noticing his frustration, Ray offers some help: “Sometimes I use wire to hold things up.”

Moojin pauses. He briefly considers the offer of help, then with a slight nod, accepts it. Ray moves closer, and together they try again, experimenting with the wire, listening to each other’s words, and watching each other’s body language. They giggle when their attempts fail, then consider other options and make new plans. When they finally succeed, they excitedly call over their teacher, Ms. Kathryn. “Look! We made a Pokémon!”

Ms. Kathryn shares their excitement. She’s also curious. “How was it working with the material?” she asks.

“It was hard, but I keep working and working and working, and then it got easy, “ Moojin says.

She questions them further: “How was working with the plasticine like working with a partner?” There is a pause, and then Ray starts: “You know, it is like our friendship. At first it was hard, but we kept working and working and working and . . . and now it is easy!” Moojin chimes in with a smile-infused “Yeah!”

Process art provides opportunities for social and emotional interactions. It can spark dialogue among teachers and children, help children form connections, and create a learning community within the classroom.

Process art provides opportunities for social and emotional interactions. It can spark dialogue among teachers and children, help children form connections, and create a learning community within the classroom.

Ray, for instance, was new to his school and anxious about being with so many other children. He and Moojin, in particular, had difficulties getting along. Yet as they worked with the materials, the two talked and problem solved together. Process art created genuine experiences of struggle, success, and connection. Ms. Kathryn’s questions about the boys’ process invited them to think more deeply and reflect on these elements.

To facilitate social and emotional development during process art, consider creating a scarcity in tools. Having to share glue sticks, scissors, or markers encourages dialogue, negotiation, and consideration of others. Also remember that many children will encounter difficulties when engaging in process art. Their work might not look like they imagined, or materials might not behave as expected. Whatever their frustration, resist the temptation to have all the answers. Instead of jumping in and providing a solution, encourage children to look for ideas among their peers (“I remember Zahra had a similar problem yesterday. I wonder if she could help you?”) and to experiment with possible solutions (“That is a big problem! I wonder if anyone has an idea about how to solve it?”). You might even consider working alongside the children and asking for help when you encounter a problem. This will signal that the class is a community of learners and that learning is a lifelong pursuit.

Process Art as a Cognitive Tool

Process art can be a powerful thinking tool. Engaging with artistic materials in playful ways—without worrying about an end product—can help shape children’s thinking. When educators are curious about the product and the process, they can support children’s ability to reflect and make meaningful connections.

For example, as the elephant-like Pokémon creature formed under the guidance of Moojin and Ray, so did their understanding of the physical world. As they attempted to keep the Pokémon’s trunk in the air, they began exploring the concept of gravity. Ms. Kathryn’s questions encouraged them to consider the physical properties of the plasticine, along with nudging them to reflect on their social interaction.

While working alongside children, teachers can model research and thinking skills by breaking down a problem into manageable parts, wondering “what if?”, and testing and evaluating ideas. Consider asking open-ended questions like

- Why did you choose this material?

- What are you learning about this material?

- What is this material helping you learn about yourself?

- What is it like working with this material with your friends?

- How is working with this material like working with your friends?

Open-ended questions can help guide teachers’ and children’s thinking, experiences, and growth across domains.

Introducing Process Art to a Preschool Setting

While process art does not require tedious hours of preparation and pre-cutting, it does require thought and planning. To help children get the most out of it,

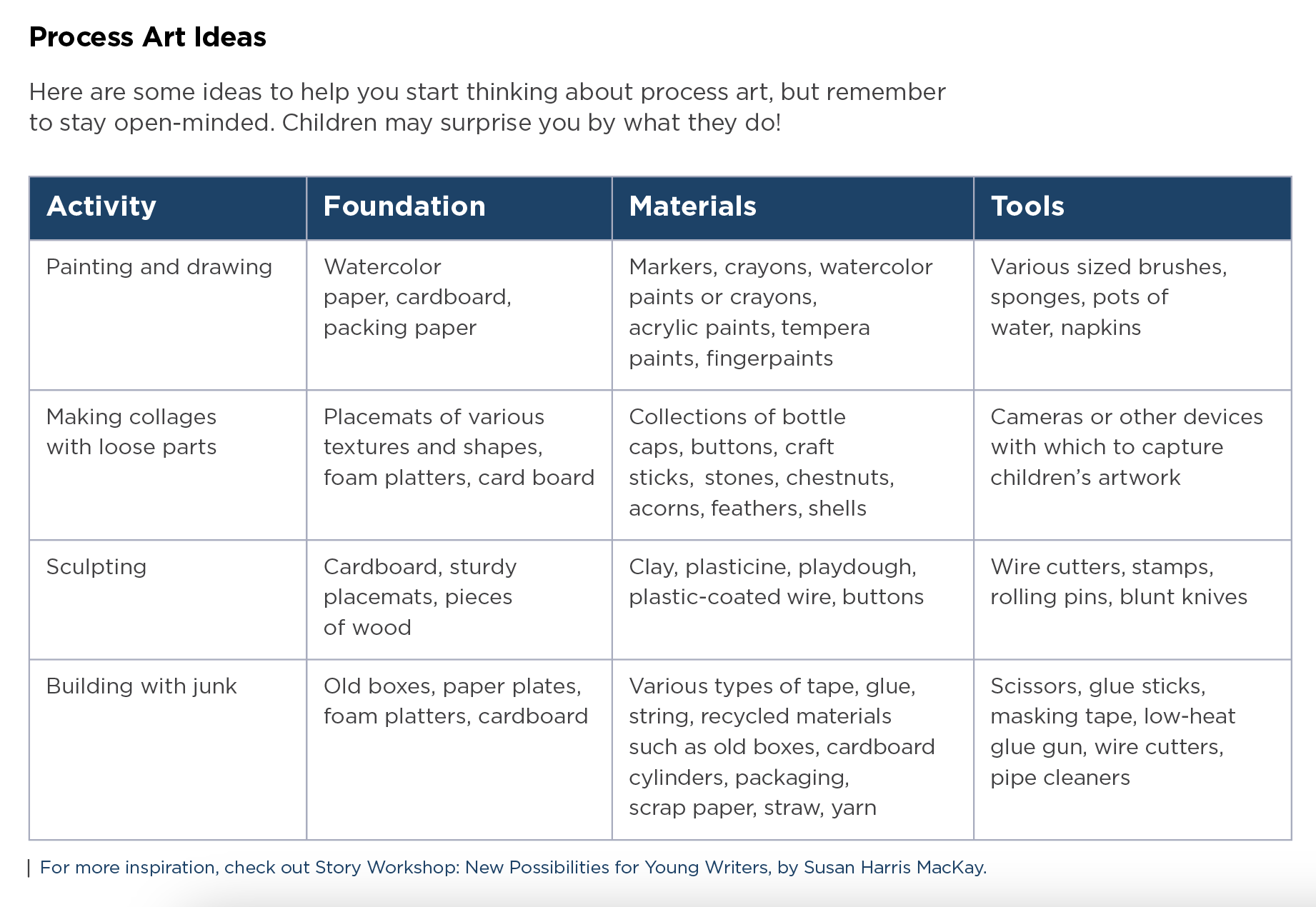

- be intentional: Rather than scattering materials around the room and waiting to see what children do with them, teachers can set up thoughtfully curated areas to spark engagement, interaction, and creative thinking. These should include a foundation, or base, for children’s work (a piece of paper, an old piece of wood, or even a stone); a medium (paint, clay, loose parts); and a variety of tools (brushes, stamps, sponges, or items from nature). Take care to set up these areas in an appealing way. This will make children feel valued and important—feelings that will be reflected in their work. (See “Process Art Ideas” below for more ideas on how to introduce process art into your setting.)

- be open-minded: Teachers may set up an area with a certain idea in mind, but their children may come up with new ways of connecting and creating. Resist the urge to step in and redirect. Instead, let the process unfold.

- document: Use photos and notes to record what children do. This will provide useful documentation during conference and reporting times. It will also give glimpses into the social, emotional, creative, and cognitive skills children are developing.

Perhaps most importantly: feel free to play! Hopefully, this article has sparked questions and ideas, perhaps even a reimagining of the possibility of art in preschool. But in the end, it has only offered words. This wouldn’t be a true ode to process art if it didn’t include an invitation to spend at least an afternoon—without expectations—in conversation with a piece of clay, or with watercolors, or with a pile of old boxes to discover the joy and possibilities process art affords you and the children you teach.

Sustainable Process Art on a Budget

Process art doesn’t require spending a lot of money on materials or using up precious resources. Start by collecting “junk”—materials and resources that can be recycled and reused. These can include cardboard cylinders, old boxes, empty yogurt containers, and wallpaper samples. In addition, materials from nature can be used as part of an art project.

Connect with families too: share with them the many benefits of process art during an open house or in a newsletter, then ask them to contribute items to your classroom. Collecting “junk” together will create a sense of community and vested interest in both the art and sustainability.

Photographs: courtesy of the author

Copyright © 2023 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See permissions and reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

Standard 2: Curriculum

2J: Creative Expression Appreciation for the Arts

Standard 3: Teaching

3E: Responding to Children’s Interests and Needs

Loretta Fernando-Smith has the joy and privilege of exploring the world with 4- and 5-year-olds at Frankfurt International School, Germany, where she works as a teacher.