What Are You Thinking? Scaffolding Thinking to Promote Learning

You are here

Lisi, a teacher of 4-year-olds at Learning Steps Learning Center in Miami, Florida, puts a manual orange squeezer in a box. Carefully, she cuts a hole in the box’s side so her children can reach in and touch the juicer without seeing it. “We are going to follow three simple steps,” she says as she introduces the activity. “First, you are going to put your hand through this hole and feel what’s inside. Second, once you touch what’s in here, your mind is going to think and make connections. Then, you’re going to go to the table and draw what you think you felt. Together, we’ll share our hypotheses.”

The children eagerly take turns inserting their hands into the box and touching the object. Lisi gives them time to make their predictions, then asks them to sit down and draw their hypotheses. Once they finish their drawings, they share and listen to each other’s ideas.

“My hypothesis is that I think it is a bus,” says Lily, holding up her drawing.

“Can you describe with details why you have that hypothesis?” Lisi asks. “What did you connect to when you touched the object inside the box?”

“When I was little, my dad had a workshop for buses,” Lily says. “So when I touched it, the bus was clean, and wheels were yellow. So I touched the wheels and they moved.”

Clara is next. She shows her drawing and says, “My hypothesis is a rainbow.”

“What makes you think it’s a rainbow?” Lisi asks.

“Because I touched it.”

“But how did you connect a rainbow to what you touched in that box?”

“I was thinking,” Clara says.

“Have you ever touched a rainbow before?” Lisi asks. “How does a rainbow feel?”

Clara thinks for a moment. “Like a slide.”

What inspires children’s curiosity? What drives active and engaged thinking in children, as illustrated in the opening vignette? Philosophers, researchers, and educators have long grappled with these questions. Historically, early childhood classrooms were built around the idea that children needed teacher-directed instructions and guidance to reach predetermined outcomes. But more recent research shows the importance of supporting children’s innate intellectual dispositions and capacities as active learners (Katz 2015). When teachers value the thinking of early learners, they intentionally design scenarios in which children are cognitively engaged. This makes the act of thinking visible to children and invites them to reflect on it.

Teachers can create and carry out a classroom culture that either fosters or discourages engaged and active thinkers. Classrooms that rely heavily on teacher-directed experiences tend to provide a set of instructions to generate predetermined answers or actions, which can hinder children’s thinking. Classrooms that incorporate child-directed experiences offer many opportunities for children to uncover their ideas, to generate questions, and to construct their own knowledge (NAEYC 2020). In our work with teachers, we implement the Visible Thinking approach to help early childhood educators intentionally plan and implement a culture of active thinking. Developed by Harvard University’s Project Zero, Visible Thinking gives teachers the tools to cognitively engage children. This article is a testimony to those teachers’ experiences and the shifts in their approaches as they focus on children’s ideas and imaginations.

Making Thinking Visible

Young children naturally produce a great deal of thinking both in and out of school. Because learning is a consequence of thinking (Ritchhart & Perkins 2008), teachers face the challenge of engaging children and seeking to draw out and understand their inner thoughts. Our research shows that when adults help children identify their thinking processes, children are likely to be more curious, more aware and reflective about their own thinking, and more likely to develop “thinking dispositions” (tendencies that guide intellectual behavior) as they encounter problems and try to solve them (Salmon 2016). Equally important, when teachers know what and how children think, they can better scaffold their learning (Ritchhart & Church 2020).

Young children naturally produce a great deal of thinking both in and out of school. Because learning is a consequence of thinking (Ritchhart & Perkins 2008), teachers face the challenge of engaging children and seeking to draw out and understand their inner thoughts. Our research shows that when adults help children identify their thinking processes, children are likely to be more curious, more aware and reflective about their own thinking, and more likely to develop “thinking dispositions” (tendencies that guide intellectual behavior) as they encounter problems and try to solve them (Salmon 2016). Equally important, when teachers know what and how children think, they can better scaffold their learning (Ritchhart & Church 2020).

Young children are ready for and deserve rich and cognitively engaging early learning experiences (Salmon 2010, 2016). Yet, as Ritchhart and Perkins (2008) say, one problem with thinking is that it’s invisible. Effective thinkers externalize their thoughts through speaking, writing, and drawing. The Visible Thinking approach invites teachers to establish a classroom culture where children’s thinking is valued, promoted, and made visible with the use of documentation. Ron Ritchhart, a researcher at Project Zero, posits that a culture of thinking takes place when both collective and individual thinking are treated in this way and actively promoted as part of the regular daily classroom experience (2015). Through intentionally planning and teaching this kind of culture, we can engage children cognitively and involve them as co-constructors of knowledge.

In his research, Ritchhart identifies eight forces that shape a culture of thinking and that teachers can use to spark curiosity in their youngest learners. We will use Lisi’s story to illustrate these forces:

- Expectations. It is important to set high expectations for thinking and learning. Teachers’ expectations are crucial when providing opportunities for students to think and express their thoughts. In Lisi’s class, she exposes children to higher-order thinking processes such as imagining, connecting, hypothesizing, and building explanations.

- Opportunities. With high expectations, teachers create opportunities for thinking and learning. Lisi designs a learning experience using an artifact (the box and hidden object) to spark children’s curiosity and engage them in deep thinking.

- Routines. These are goal-centered strategies designed to promote, scaffold, and provide patterns of thinking. Lisi creates a routine (touch-think and connect-hypothesize) to regularly engage her students in the process of thinking. Through the routine, Lisi’s children use their senses to explore, imagine, make connections, hypothesize, and share ideas.

- Language. By using a language of thinking, teachers offer students a vocabulary to describe and reflect on thinking. Lisi introduces a new language of thinking with words and phrases such as hypothesizing and making connections.

- Time. Allowing time for thinking and reflecting is essential. Lisi gives children time to process their ideas, express them, and share them with their peers.

- Modeling. Teachers must model thinking and learning. Modeling who we are as thinkers and learners encourages us to discuss, share, and make the process of our thinking visible. Lisi introduces her classroom activity by modeling the process and type of thinking her students will use.

- Interactions. Teachers promote and encourage others to respect children’s contributions. Showing respect for and valuing each other’s contributions of ideas in a spirit of ongoing, collaborative inquiry are important. In Lisi’s class, children listen to each other, ask questions, and learn to value the different ideas that emerge from the activity.

- Environment. Arranging the classroom space to facilitate thoughtful interactions ensures that the learning environment displays representations of children’s thinking. Lisi exhibits her children’s hypotheses drawings on her classroom walls. She uses this documentation to build on the next activity.

Transforming Expectations and Questions to Attain a Culture of Thinking

To promote a deep-thinking classroom culture, teachers must learn how to ask strategic questions. Questions set the stage for and guide thinking. They deepen learning, build a growth mindset, and help students become more aware of their own thinking processes (Costa & Kallick 2015). However, they need to be the right kinds of questions.

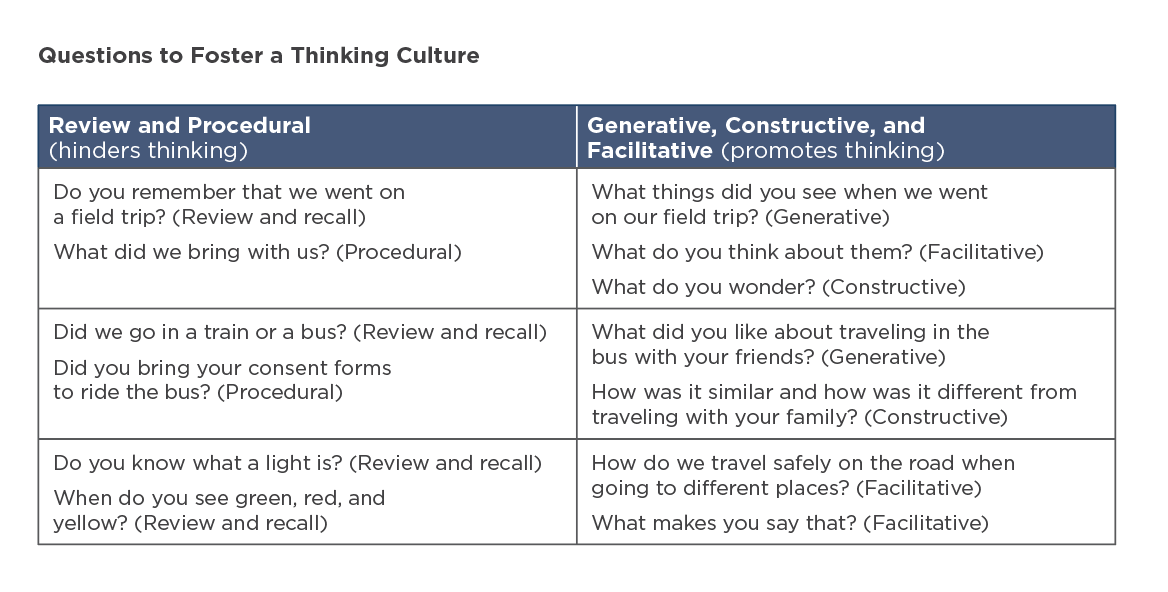

Most classroom questions fall into one of five typologies (Ritchhart 2015):

- Review. Recalling and reviewing knowledge and information

- Procedural. Directing the work of the class, going over directions and assignments

- Generative. Exploring the topic, asking authentic questions

- Constructive. Building new understanding, extending and interpreting, connecting and linking, focusing on big ideas, and evaluating

- Facilitative. Promoting learners’ own thinking and understanding, elaborating, reasoning, and justifying

When teachers center their questions on review and procedural, children can quickly lose interest. Teachers who ask children simply to review what they know or to parrot back directions miss out on rich opportunities to cognitively engage and challenge their students to think beyond the obvious. Neither the teacher nor the children build upon each other’s contributions. To transform these types of questions into a more productive dialogue, teachers should think about the effect their questions will have on children’s responses: how can they formulate questions that will make children’s thinking visible? Good questions emerge from listening carefully to children, building from their ideas and interests, and moving forward. (See “Questions to Foster a Thinking Culture," below.) As Duckworth says, having wonderful ideas “implies generating or owning ideas, and ownership stands in contrast to being told what you ought to understand” (Meek 1991, 30).

Renata teaches 3-year-olds at a South Florida preschool. She has grappled with ways to engage her children and promote their curiosity and ideas. A recent discussion about a field trip devolved into fidgeting, boredom, and disengagement. Upon reflection, she realizes her expectations were too low. She was asking children to recall and recite basic facts of the field trip rather than challenging them to build new understandings, elaborate on their thoughts, and make connections with their own and each other’s ideas.

After careful reflection, Renata gathers her 3-year-olds and begins discussing the field trip again. Only this time, she focuses on asking authentic questions designed to engage the children in her class. “Karla,” she says, “on our trip, you saw a dark cloud that made you think it was going to rain. What else did you see?”

“I saw a plant,” Karla says, recalling the field trip.

“What makes you say that it was a plant?” Renata asks, jotting down the child’s comments.

Olivia pipes up. “Because you can’t take them off when you pull their hair.”

“The plant’s hair?” Renata asks, picking up a plant to show the children. “What is the part of the plant that is the hair? If I show you this plant, what is its hair?”

This conversation illustrates how Renata is building on Karla’s ideas and theories. Her questions are more generative and constructive. She values her students’ contributions and ideas, and she shows respect for Karla’s description of the plant. When Renata reflected on this interaction, she said: “I learned that as children share their ideas and exchange viewpoints, they develop different modes of thinking. By empowering children, the interactions change, the conversation evolves from children’s ideas, and the teacher’s expectations change when children make visible what they know and think about the world.”

Offering Opportunities to Think

Too often, activities in early childhood settings are characterized by a teacher-centered approach: teachers design step-by-step activities and expect similar outcomes from all children. By contrast, developmentally appropriate practice encourages teachers to build on each child’s multiple assets and to create opportunities for each child to exercise choice and agency within the context of a planned environment (NAEYC 2020). In such a setting, educators recognize that children are active constructors of their own understanding of the world around them. They understand that children benefit from initiating and regulating their own learning activities. An appropriate curriculum for young children is one that includes a focus on supporting children’s inherent intellectual dispositions (Katz 2015). Teachers who see the potential of cognitively engaging children empower them to become more creative, autonomous, and intentional.

Lisi, the teacher from the opening vignette, has witnessed this progression in her own teaching. When she began at Learning Steps, she focused her efforts on introducing numbers and letters and using the calendar as a recall activity. When challenged to incorporate activities that would nurture and advance children’s thinking, she initially viewed them as a time constraint and “just another activity.” However, once she began giving her students the chance and encouragement to think and verbalize their thoughts, she witnessed how readily they engaged in higher-order thinking skills: They made connections and formed hypotheses; they connected their imaginations to experiences; they used physical objects to represent imagery. When challenged with probing, supportive, meaningful questions, their thinking went beyond the parameters that adults often set for young children. As Duckworth says, “To teach is understanding someone else’s understanding” (Meek 1991, 32).

Taking Time to Observe and Reflect

To have a meaningful conversation with a child, adults need to know what the child thinks. Forman and Hall (2005) stress the importance of observing and documenting children with written notes and recordings or observing and analyzing children’s own work. This helps teachers learn about each child’s interests, skills, and thinking. Children are competent learners, the researchers write, but teachers must slow down, carefully observe, and study their documented observations. (For more about documenting observation, see “Learning Stories: Observation, Reflection, and Narrative in Early Childhood Education,” by Isauro M. Escamilla.) By revisiting an experience with a child and putting that experience into words, adults begin to understand the theories that influence a child’s actions or interests. Lisi, for example, designed an activity to introduce two thinking concepts: connections and hypotheses. The children’s drawings uncovered their hypotheses, and when they shared the thoughts behind their drawings, Lisi learned about the connections her children made to their personal experiences. Similarly, Renata’s documentation helped her understand her children’s theories about plants. Both observations were valuable for the teachers to scaffold their children’s understanding.

When teachers have high expectations of their students as thinkers, children receive the message that their thinking is valued. Moreover, teachers gain ownership and power to make intentional decisions to nurture children’s thinking dispositions. To ensure that this happens, reflection is necessary. Ritchhart’s (2015) typology of classroom questions is a great resource for teachers to use to analyze their interactions with children. Additionally, they can ask themselves the following questions:

- What type of thinking is my question generating?

- How can I formulate questions that cognitively engage children?

- How can I listen to children and understand their thinking?

- How does documentation inform me about children’s thinking?

- How can I dig into children’s minds to discover their prior knowledge, interests, and theories?

Teachers’ interactions with children are deeply connected to their goals for teaching. They also are tied to their own expectations about children as thinkers and learners. When teachers understand children’s thinking, they can spur them to think in new and innovative ways.

Photographs: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2021 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Costa, A., & B. Kallick. 2015. “Five Strategies for Questioning with Intention.” Educational Leadership 73 (1): 66–69.

Forman, G., & E. Hall. 2005. “Wondering with Children: The Importance of Observation in Early Education.” Early Childhood Research and Practice 7 (2).

Katz, L. 2015. “Lively Minds: Distinction Between Academic Goals Versus Intellectual Goals for Children.” Defending the Early Years. deyproject.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/dey-lively-minds-4-8-15.pdf

Meek, A. 1991. “On Thinking About Teaching: A Conversation with Eleanor Duckworth.” Educational Leadership 48 (6): 30–34.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP).” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents

Ritchhart, R., & D. Perkins. 2008. “Making Thinking Visible.” Educational Leadership 65 (5): 57–61.

Ritchhart, R. 2015. Creating Cultures of Thinking: The 8 Forces We Must Master to Truly Transform our Schools. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ritchhart, R., & M. Church. 2020. The Power of Making Thinking Visible. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Salmon, A. 2010. “Tools to Enhance the Young Child’s Thinking.” Young Children 65 (5): 26–31.

Salmon, A. 2016. “Learning by Thinking During Play: The Power of Reflection to Aid Performance.” Early Child Development and Care 186 (3): 480–96.

Angela K. Salmon, PhD, is associate professor of early childhood education at Florida International University in Miami, Florida. She is the founding leader of the Visible Thinking South Florida Initiative. Her research draws from her experience coaching teachers in the implementation of cutting-edge, research-based ideas that promote thinking through meaningful experiences centered in play, children’s rights, and global competencies. [email protected]

María Ximena Barrera, MEd, is an adjunct professor at Florida International University in Miami, Florida. She is an online co-instructor at Project Zero at Harvard Graduate School of Education in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She is the director of program development of FUNDACIES, a professional development organization for educators. [email protected]