Using Story Circles, Art, and Play to Support Children’s Responses to Stress and Trauma

You are here

Berto, a 4-year-old preschooler from an immigrant family, sits at the edge of Teacher Sofia’s story circle. Sofia and her coteachers have engaged children in this small-group storytelling activity over time, so Berto and his classmates know that they will be taking turns telling a story of their choosing. When it is his turn, Sofia calls him closer. Moving fluidly between Spanish and English, Berto tells of a recent experience.

Sofia: Ven aquí. Ven con mi aquí. (Come here. Come by me here.)

Berto: I don’t give historia (story).

Sofia: (offering encouragement) ¿Okay, un animal? ¿No? ¿Okay, qué también? ¿Qué paso en tu casa? (Okay, an animal? No? Okay, what else? What happened in your house?)

Berto: En la noche era tiros. (In the night, it was gunshots.)

Sofia: Cómo? (How?)

Berto: Con pistolas. Y herido los niños. Y si no contesta, los matan. (With guns. And hurt children. If you don’t answer, they kill them.)

Sofia does not know how much of what Berto describes is real, a dream, or based on overheard talk. In the weeks prior to his story, several high-profile immigrant sweeps have occurred in the community, and Berto’s family has shared that they are uncertain what to do. Their family, like so many, has members in the United States with different legal statuses. Even though Berto’s school has tried to reassure families that it is a safe space, rumors are running rampant, and many families are keeping their children at home.

Gun violence, raids on immigrants, divisive rhetoric, global pandemics, rising economic stress—few spaces feel safe today. If adults feel uncertain, how do young children find ways to make sense of and process the feelings of fear and unease that have overtaken so many communities and families?

Stress and trauma in young children are at a crisis level: research shows that 26 percent of children in the United States witness or experience stressful or disruptive events before age 4 (Erdman & Colker, with Winter 2020). Stressors can include everyday fears (monsters or the dark), ongoing stress (uncertain access to food or housing), or traumatic experiences (exposure to family or community violence). These, in turn, can disrupt a child’s sense of safety, power, and personal value, leading to withdrawal, developmental regression, or changes in emotional regulation (NCTSN 2023).

Early childhood educators can help mitigate the effects of stress and trauma by creating caring, trauma-informed learning communities that offer children the opportunities and agency to process their experiences. Drawing on a larger research study examining language development in the context of story circles (Flynn 2021; Flynn et al. 2021; Flynn 2022), this article outlines how teachers can braid storytelling—and by extension, art and play—into their learning routines to help children make sense of their thoughts, feelings, and experiences. This approach supports children to develop their innate strengths while relying on the learning community as a stable resource for coping with stress, trauma, and the everyday fears that all young children face. Drawing on expertise in language development, social work, and early childhood mental health, we (the authors) explain how to protect time and space for children to express themselves through story.

Stress and Trauma in Early Childhood

Trauma occurs when “the strengths inside you and the resources around you can’t respond to a threat” (Adelman et al. 2015). It can stem from a frightening, dangerous, or violent event that a child observes or experiences (NCTSN 2023) as well as stressful or disruptive situations that threaten a child’s sense of security and stability (Schonfeld, Demaria, & Kumar 2020). Children can be affected by trauma directly or indirectly (Erdman & Coker, with Winter 2020); they can even be impacted by an event that was experienced by their families before they were born (Yehuda & Lehrner 2018).

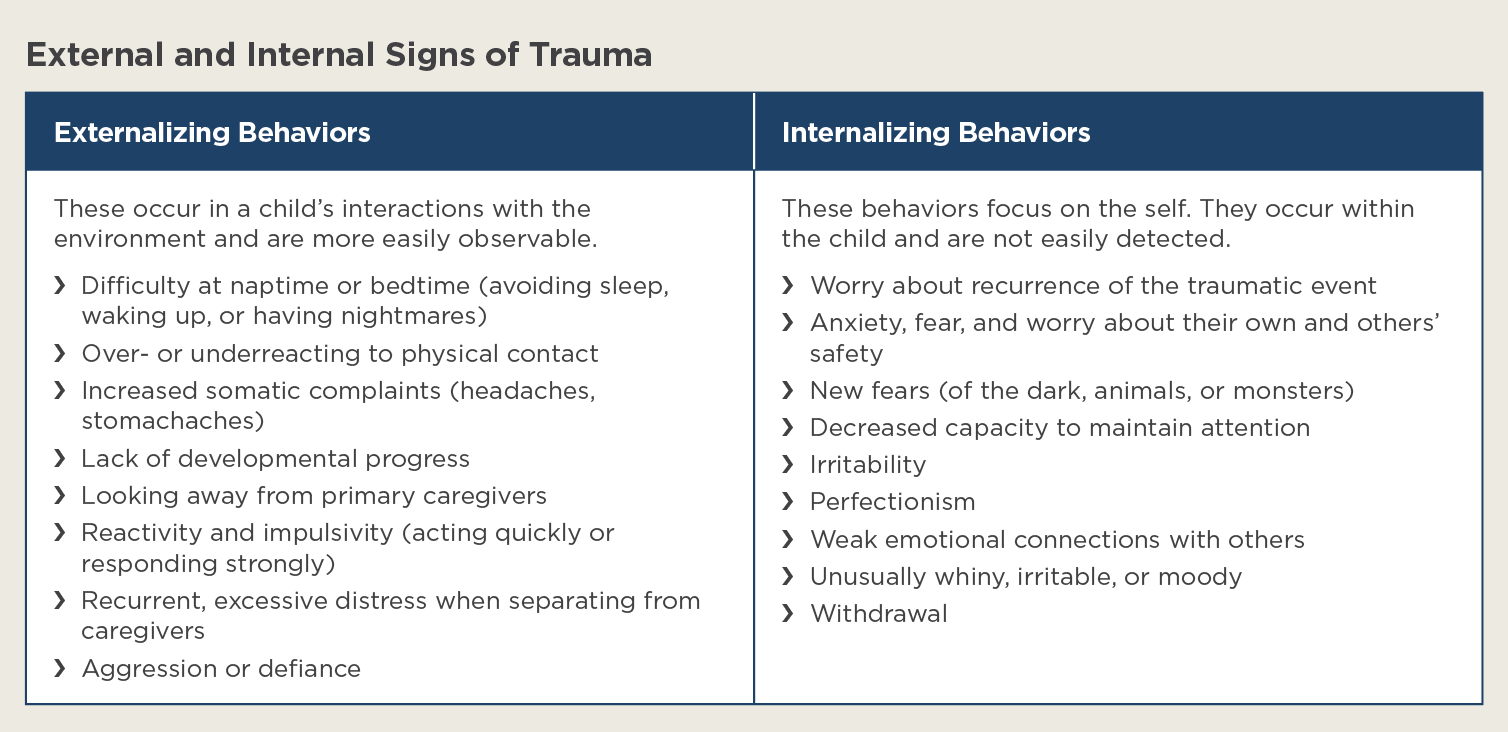

Signs and symptoms of distress in young children can manifest in a variety of ways, yet they often look different from the ways adults express difficulties (NCTSN 2023). A helpful way to identify signs of stress or trauma is to separate them into externalized (anyone can see) and internalized (happening within the child; not easily detected) behaviors or ways in which distress is expressed. (See “External and Internal Signs of Trauma” below.) Importantly, children with internalizing behaviors often receive less support because the signs of distress are less visible. Adults often assume that expressions of internal distress are willful or under a child’s effortful control (Splett et al. 2019; VanMeter, Handley, & Cicchetti 2020).

Because early childhood teachers educate and care for children over the course of a year (or more), they are in a privileged position to observe and help respond to the changes in behaviors, development, and learning that may occur due to stress or trauma (Erdman & Colker, with Winter 2020; NCTSN 2023). Working closely with families, quality early childhood programs consistently monitor the social, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral development of the children in their care. Developmental screening tools like the Ages and Stages Questionnaires (Squires & Bricker 2009) can provide important information about children’s development as well as guide families on how to support their children’s growth or when to seek further resources and services.

Creating Caring Communities for Children Experiencing Trauma

Children who experience ongoing stress or trauma often have their sense of safety, power, and personal value disrupted or harmed (SAMHSA 2014). Early childhood educators and environments are a vital support for these children because they provide a stabilizing resource for processing and healing.

Vivian Paley, famed early childhood educator, noted that teachers have a responsibility to provide a “sensible world” when outside forces stress children and families (Paley 1990, 115). Developmentally appropriate practice connects to this idea, with its emphasis on caring and equitable learning communities. As early childhood educators listen to and acknowledge children’s feelings, they make every effort to help each and every child feel emotionally and physically safe. They are prepared to recognize signs of stress and trauma and to provide frequent, explicit, and consistent reminders that adults are working to keep children safe (NAEYC 2020).

Teachers can provide caring communities in several ways. One is to ensure that children have the opportunity to exercise their agency (NAEYC 2020). Agency is an equity-centered practice that encourages children to interact with materials and each other in open-ended, child-directed ways (Jones, Fowler, & Adair 2023). As children make choices about and influence the context of their learning activities, they gain a sense of power—particularly when deciding what and how to share about traumatic experiences.

Other ways to ensure a caring community of learners include:

- offering predictable structures through regular routines

- creating reminders to help children anticipate transitions or changes to the routine

- establishing clear, consistent boundaries

- organizing and setting out materials to position children as active in their own learning

- providing an atmosphere that supports and sustains a calming state

- ensuring that children see themselves and their families reflected in books, music, and other learning materials

- listening to understand and affirm children rather than questioning them or minimizing their expressions

Children who have experienced trauma can learn and grow in positive ways, building strengths from dealing with early stressors. Positive relationships with teachers can help to protect children from the effects of stressful or traumatic events, especially when sensitive and responsive child-teacher interactions exist (Sciaraffa, Zeanah, & Zeanah 2018). Caring relationships support children’s resilience despite early adversity.

Supporting Children Through Storytelling, Art, and Play

Storytelling, art, and play support children in expressing and processing everyday fears, ongoing stress, and/or traumatic events. Through drawing, play, and engagement with open-ended materials, children may communicate concerns that they are less able to talk about directly (Ippen, Lieberman, & Van Horn 2005; Schonfeld, Demaria, & Kumar 2020). When adults recognize the real-world significance of these activities, they can better understand how children view events (Desmond et al. 2015). By attuning their attention to the meaning and importance of stories, art, and play, teachers position children to reclaim a sense of agency and power in responding to the uncertainty of sometimes overwhelming external forces.

While studying children’s participation in a teaching activity called story circles and its social, emotional, and language learning potential, we were struck by how deeply intertwined the children’s stories were with their art and ongoing play. Through their stories, children amplified the drama of their daily pretend play and shared poignant and sometimes painful experiences about their family and community lives. From the story circle to the playground to the art easel, we documented children’s growing capacity with language (Flynn 2021), their growing relational bonds (Flynn 2022), and the unanticipated amount of emotional processing.

Story circles have a long history of use for community building and engagement. They are considered a culturally responsive teaching activity because they draw on Indigenous talking circles (MacLean & Wason-Ellam 2006) and Black activism and cultural forms (Randels 2005; Michna 2009). Story circles were used with high school students in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina (Randels 2005); they also have been used in faith-based and therapeutic settings (Williams-Clay, West-Olatunji, & Cooley 2001).

In early learning settings, story circles consist of groups of four to six children who meet weekly throughout the program year. These groups are made up of both mono- and multilingual speakers so that children can learn from each other. The groups stay consistent in terms of their membership to support children in developing and deepening ongoing shared story themes. Children take turns telling a story of their choosing and, when possible, in their preferred language. Teachers help facilitate turn taking and listen to children but do not attempt to extend children’s stories through questions or prompts. Instead, children tell longer and more complex stories over time by repeatedly engaging in the activity and listening to each other (Flynn 2021). Teachers respond in encouraging ways, thanking a child for their story or responding with verbal or nonverbal affirmation.

Story circles’ repeated and consistent use helps create a sense of predictability—a key element of a caring learning community. They can be particularly effective in helping children process trauma because telling stories about an event helps children make sense of and cope with what happened (Ippen, Lieberman, & Van Horn 2005). As teachers listen to and affirm these stories, they communicate the significance of both the experience and of a child’s everyday fears, ongoing stress, or experiences of trauma. Teachers can plan art and play opportunities to make use of and further explore ideas from these stories as part of a child’s ongoing learning. They can also plan and implement individualized activities, instruction, and supports, including in conjunction with specialists, to respond to a child’s ideas and feelings expressed during story circle.

Following, we present examples of the power of coupling consistent, sensible learning communities with open-ended expressive opportunities.

Processing Everyday Fears and Uncertainties

Children express everyday fears as part of a healthy emotional range. Indeed, sharing their thoughts, feelings, and interior lives helps promote healthy social and emotional development (Ippen, Lieberman, & Van Horn 2005; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2010).

Many of the children we observed used story circles, art, and play to relay everyday fears and uncertainties by telling about their dreams. Consider Destiny, a 4-year-old who painted a picture at the beginning of the year and shared, “This is about bad dreams and monsters coming. The monsters eat me!” During story circle, she thought through a time when she dreamt about monsters and a time when she did not:

I had a dream at my mommy’s house. I was in her bed. And I slept in my mom’s bed. And I had a dream of a monster. Then, um, then I washed my hands. Then I went to go potty. And I, I peeked in my mom’s room. On accident. And I and my brother was gone with my mom’s sister. Then I spent the night, and I didn’t have no dreams there. All done.

On the playground, Destiny continued to process her fear: She and her cousin, Gabriel, chased each other, pretending to be monsters. The two entered a small playhouse, then began pretending to be a family. Gabriel played the brother and began to build a bed while Destiny organized the other furniture as the two prepared to go to sleep. Their play juxtaposed the drama of monsters with the orderly calm of preparing to rest with family.

Just as with adults, children’s dreams often combine fantastic and realistic fears. For example, Caleb, a 4-year-old boy who told stories about familial love, missing his parents, the reality of death, and the need for strength, told a story one week about caution tape at his home:

And when the people come to my house. I kick them out of my house.

A month later, he shared this in story circle:

I just dreamed about a story. When I was a baby, I dreamed about scary monsters. My dad was in it, and I was in it. And last time, I dreamed about something on fire. Like a house. And you. And the water. And the fire truck people. They put the fire out. And it was too on fire. And that’s the end.

Caleb’s teachers affirmed the value of his story by listening closely, echoing his emotional language, and making appropriate comments like “Sounds scary.” By repeating his words, they showed Caleb that he was heard and understood. Through the predictable activity of a story circle, Caleb had the agency to share what felt relevant to him. His teachers’ responses affirmed that his contributions were valued and respected as an important part of his healing process.

If Destiny dreamed about monsters, Caleb sought to embody them. He stomped through play with an energy and force appreciated by his playmates but often concerning for his teachers. The overwhelming emphasis of his stories—both fantastic and realistic—was destruction, punctuated by a desire to be close to and share experiences with his family. (“My daddy showed me a rainbow”; “I went to a dinosaur show. I went and seen a bunch of dinosaurs. My mom took me everywhere.”)

Teachers often miss the signs of a child’s chronic stress or trauma. When children upend blocks, roar like lions, or wrestle unwilling classmates, their behavior can be mischaracterized as disruptive or challenging. But rather than misbehavior, it may be a symptom of the kind of hyperarousal experienced by children exposed to the ongoing stressors of economic uncertainty or traumatic events occurring in the home, school, or community (Vericat Rocha & Ruitenberg 2019). Opening a learning program’s space for storytelling and talk helps teachers see a child more completely and determine how to respond: Caleb is a 4-year-old who sees caution tape at home and dreams of a burning house but who is closely connected to family. When teachers have the time to listen to and hear children, they often realize those children are far more aware of familial stress than adults may assume. They can then plan and use strategies, activities, and materials that effectively and equitably respond to each child’s context, which may involve other early childhood professionals and resources. An infant and early childhood mental health consultant can help teachers create the classroom conditions necessary for success, including identifying when therapeutic supports outside the learning setting may be needed (NCECHW 2023).

Opening space for storytelling and talk helps teachers see a child more completely and determine how to respond.

Grappling with Violence

Nearly all children express everyday fears and uncertainties—both real and imagined—over the course of an early childhood program’s year (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2010). However, some children have experienced real violence at a young age. Immigrant and refugee children, for example, may have witnessed violence through arduous immigration experiences. Abia, a 4-year-old from a recent immigrant family, was a confident classroom leader and frequent initiator of popular games. One day, she and the other children made animal masks as part of an ongoing class theme. Abia and two of her friends made cat masks. After the art activity, Abia continued pretending to be a cat, meowing and trying to curl up in her teacher’s lap long after her classmates had drifted off to other play. This kind of proximity seeking is common among children who have experienced stressful or traumatic events (Sciaraffa, Zeanah, & Zeanah 2018). Later, Abia shared this during story circle:

Abia: Somebody putted a bomb in my grandpa’s car. Then he got died. The end. But the rest of the family didn’t die.

Teacher Hannah: And where was this at, Abia?

Abia: In Iraq.

Hannah: In Iraq. Of course. (Hannah turns to Jessica, who is taking research notes.) But she doesn’t know.

Abia: (forcefully) In Iraq.

Jessica: I’m sorry to hear about that, Abia.

Abia: Because I used to live there. But I now traveled here.

Hannah: Did your family, did your dad get to see him? Did you get to go see his family?

Abia: Uh. No. We just traveled here. When, when I was 3.

Hannah: Yes. Yes.

While Hannah initially assumed that Abia was too young to remember or understand her early adverse experience (a common reaction from adults), Abia asserted that she did remember. Jessica’s empathetic response encouraged Abia to say more. Hannah then followed with questions to help her better understand the situation without leading Abia to recount painful or violent details unless she chose to do so. It is important for teachers to remember not to ask children to recount violent or traumatic experiences, which can force them to relive painful and overwhelming feelings. Instead, their task is to create an environment that is open and affirming should children choose to use the classroom to express and reflect on troubling times.

While it is common for teachers to exclude a child who shares adverse events from an activity or even the program in an attempt to protect other children from traumatic experiences, such actions remove the child from the very support and consistency they most need (NCECHW 2023). For some children, the teacher may be one of the only dependable, safe, and caring relationships they can consistently rely on. Thus, it is critically important that children do not feel punished for expressing their feelings (Sciaraffa, Zeanah, & Zeanah 2018). Responses that show interest, concern, and care while allowing the child to control what and how to share a traumatic experience reinforce the message that teachers are a reliable source of support but that, ultimately, children have the power to name for themselves the experiences that matter and what they want to share (Ippen, Lieberman, & Van Horn 2005).

The most important action a teacher can take when children recount painful or distressing experiences is to respond calmly and empathetically (Sciaraffa, Zeanah, & Zeanah 2018). Rather than minimizing a child’s feelings, they should use affirming responses that acknowledge a child’s feelings, respect their efforts to cope with difficulty, and emphasize safety (“That sounds scary. Just remember you are safe here”; “I can see that makes you feel sad. It is okay to feel that way”). This approach shows children that they can rely on their teachers for consistent, predictable care. It also serves as a buffer to other children in the room who are hearing about these stressful events (Bulotsky-Shearer et al. 2020a; Bulotsky-Shearer et al. 2020b). Educators’ own emotional regulation in the face of adversity or stress has a major impact on the children in their learning settings (Phillips et al. 2022; Pekrun 2021).

Making Sense of Experiences

Just as Destiny, Caleb, and Abia used storytelling, art, and play to work through and process their scary feelings, children can use these tools to work through and reframe difficult experiences. For example, Abia used four frog characters from a classroom book to create a story in which she reflected on the experience of moving from one country to another.

Once a time again. There was a little frog. Four frogs. One was yellow. One was pink. And one was white. And one was yellow. And their mom said they had to go to another country. Well, they couldn’t go. Only if they tried to fly an airplane. Well, they said they had to do it on their own. Well, they couldn’t. So they said, “Let’s do one together.” The end.

Repurposing known stories gives children another opportunity to reflect on and process traumatic or stressful experiences. Drawing on a favorite book, Abia introduced the four frogs in a way similar to the books before introducing a fictional frog mom who announced the need to go to another country in an airplane. In this case, Abia concluded with a community-focused lesson: it can be easier to do things together rather than on one’s own.

Play also helps children externalize and make sense of experiences. On a day when their school had a lockdown drill, children and teachers huddled in a bathroom to practice for the presence of a “dangerous person”—once unthinkable, but now routine. Afterward on the playground, Emma and Mariana cradled imaginary babies in their arms.

Emma: You have to run to safety!

Mariana: I’m here.

Emma: We have to go there together. (The two girls run to the other side of the playground, still pretending to hold their babies, as they escape an imaginary antagonist.)

Even small play scenes like the one between Emma and Mariana hold value for children. This is because play helps children express what they think and feel, reduce their fears, and regain a sense of competence and power in the face of external forces (Erdman & Colker, with Winter 2020).

Conclusion

Storytelling, art, and play offer much needed spaces for children to talk about trauma and other stressful experiences. When teachers create caring, trauma-informed learning communities, they disrupt the cascading effects of these experiences and instead offer spaces where children feel free to share their concerns, fears, and real and fantastic dreams.

To encourage children to use their agency through storytelling, art, and play, teachers can create their own sensible learning communities by preparing themselves, their learning environments, and the materials in their settings:

- To help develop their knowledge about trauma and trauma-informed practices, educators can seek out research-backed resources on the topic. NAEYC publications examine trauma-informed care and highlight teaching strategies to support and empower children experiencing trauma. Of specific note are the July 2020 issue of Young Children and the 2020 book Trauma and Young Children: Teaching Strategies to Support and Empower. Other resources include the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative (traumasensitiveschools.org) and the National Black Child Development Institute (nbcdi.org). The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (nctsn.org) also offers guidance for educators, including when a referral should be made for additional help. (See nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources//suggestions_for_educators.pdf.)

- Learning settings with reduced noise and opportunities for quiet times support both teachers and children to maintain a calm state. A quiet corner can serve as a sheltered space. Lighting that can dim, calm and soothing colors and decorations, and clutter-free counters also help the eyes to visually rest.

- Equity-centered materials comfort children by ensuring that they see themselves and their families represented. Children thrive when they have access to crayons and paints in different skin tones; music that reflects different racial, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic communities; and books about and authored by people of color. The Colors of Us, by Karen Katz, Happy Hair, by Mechal Renee Roe, and ABC I Love Me, by Miriam Muhammad, offer options for any equity-centered learning community library.

What action steps will you take to create the kind of consistent, caring learning community that supports all children by centering the needs of those most marginalized amongst us: Children who have experienced ongoing stress or traumatic events?

Photographs: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2023 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Adelman, L., C. Herbes-Sommers, J. Rutenbeck, & L. Smith. 2015. The Raising of America: Early Childhood and the Future of Our Nation. Advance release ed. San Francisco, CA: California Newsreel and Boston, MA: Vital Pictures. raisingofamerica.org.

Bulotsky Shearer, R.J., K. Bichay-Awadalla, J. Bailey, J. Futterer, & C.H. Qi. 2020a. “Teacher-Child Interaction Quality Buffers Negative Associations Between Challenging Behaviors in Preschool Classroom Contexts and Language and Literacy Skills.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 40 (3): 159–171.

Bulotsky-Shearer, R.J., V.A. Fernandez, K. Bichay-Awadalla, J. Bailey, J. Futterer, & C.H. Qi. 2020b. “Teacher-Child Interaction Quality Moderates Social Risks Associated with Problem Behavior in Preschool Classroom Contexts.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 67: 101103.

Desmond, K.J., A. Kindsvatter, S. Stahl, & H. Smith. 2015. “Using Creative Techniques with Children Who Have Experienced Trauma.” Journal of Creativity in Mental Health 10 (4): 439–455.

Erdman, S., & L.J. Colker. With E.C. Winter. 2020. Trauma and Young Children: Teaching Strategies to Support and Empower. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Flynn, E.E. 2021. “’Rapunzel, Rapunzel, Lanza Tu Pelo’: Storytelling in a Transcultural, Translanguaging Dialogic Exchange.” Reading Research Quarterly 56 (4): 643–658.

Flynn, E.E. 2022. “Enacting Relationships Through Dialogic Storytelling.” Linguistics and Education 71:101075.

Flynn, E.E., S.L. Hoy, J.L. Lea, & M.A. García. 2021. “Translanguaging Through Story: Empowering Children to Use Their Full Language Repertoire.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 21 (2): 283–309.

Ippen, C.G., A.F. Lieberman, & P. Van Horn. 2005. After a Crisis: How Young Children Heal. Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. nctsn.org/resources/after-crisis-helping-young-children-heal.

Jones, N.N., A.T. Fowler, & J.K. Adair. 2023. “Assessing Agency in Learning Contexts: A First, Critical Step to Assessing Children.” Young Children 78 (1): 16–23.

MacLean, M., & L. Wason-Ellam. 2006. When Aboriginal and Métis Teachers Use Storytelling as an Instructional Practice. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Saskatoon Catholic Schools, University of Saskatchewan.

Michna, C. 2009. “Stories at the Center: Story Circles, Educational Organizing, and Fate of Neighborhood Public Schools in New Orleans. American Quarterly 61 (3): 529–555.

NAEYC. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents.

NCECHW (National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness). 2023. “Understanding and Eliminating Expulsion in Early Childhood Programs.” Retrieved from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/publication/understanding-eliminating-expulsion-early-childhood-programs.

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. 2010. Persistent Fear and Anxiety Can Affect Young Children’s Learning and Development: Working Paper No. 9. Cambridge, MA: Center on the Developing Child. developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/persistent-fear-and-anxiety-can-affect-young-childrens-learning-and-development.

NCTSN (The National Child Traumatic Stress Network). 2023. “About Child Trauma.” Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/about-child-trauma.

Paley, V. 1990. The Boy Who Would Be a Helicopter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pekrun, R. 2021. “Teachers Need More Than Knowledge: Why Motivation, Emotion, and Self-Regulation Are Indispensable.” Educational Psychologist 56 (4): 312–322.

Phillips, D.A., J. Hutchison, A. Martin, S. Castle, & A.D. Johnson. 2022. “First Do No Harm: How Teachers Support or Undermine Children’s Self-Regulation.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 59: 172–185.

Randels, J. 2005. “After the Storm: The Story Circle.” Education Week. blogs.edweek.org/teachers/randels.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2014. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Rockville, MD: SAMSHA. ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf.

Schonfeld, D.J., T. Demaria, & S.A. Kumar. 2020. “Supporting Young Children After Crisis Events.” Young Children 75 (3): 6–15.

Sciaraffa, M.A., P.D. Zeanah, & C.H. Zeanah. 2018. “Understanding and Promoting Resilience in the Context of Adverse Childhood Experiences.” Early Childhood Education Journal 46: 343–353.

Splett, J.W., M. Garzona, N. Gibson, D. Wojtalewicz, A. Raborn, & W.M. Reinke. 2019. “Teacher Recognition, Concern, and Referral of Children’s Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems.” School Mental Health 11: 228–239.

Squires, J., & D. Bricker. 2009. Ages & Stages Questionnaires, Third Edition (ASQ-3): A Parent-Completed Child Monitoring System. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.

VanMeter, F., E.D. Handley, & D. Cicchetti. 2020. “The Role of Coping Strategies in the Pathway Between Child Maltreatment and Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors.” Child Abuse & Neglect 101:104323.

Vericat Rocha, Á.M., & C.W. Ruitenberg. 2019. “Trauma-Informed Practices in Early Childhood Education: Contributions, Limitations and Ethical Considerations.” Global Studies of Childhood 9 (2): 132–144.

Williams-Clay, L.K., C.A. West-Olatunji, & S.R. Cooley. 2001. “Keeping the Story Alive: Narrative in the African-American Church and Community.” Paper presented at the American Counseling Association conference, in San Antonio, TX. ERIC, ED462666.

Yehuda, R., & A. Lehrner. 2018. “Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma Effects: Putative Role of Epigenetic Mechanisms.” World Psychiatry 17 (3): 243–257.

Erin Elizabeth Flynn, PhD, is an associate professor of Child, Youth, and Family Studies at Portland State University in Oregon. A former preschool teacher, Erin studies the social, emotional, and linguistic power of engaging young children in storytelling. [email protected]

Selena L. Hoy, MSW, is the community services manager at TELL Japan, a nonprofit in Tokyo dedicated to suicide prevention and mental health support. Selena received her MSW from Portland State University, where she conducted research in early education classrooms. [email protected]

Dalia Avello-Vega, PsyM, MA, MRes, IMH-E, is a professor of practice with Trauma Informed Oregon at Portland State University. Her work is centered on infant and early childhood mental health, with a special focus on adversity, policy, and implementation.

Keyonia Williams, LCSW, specializes in Afrocentric mental health services that include coaching and consulting for individuals, groups, organizations, and families. As a mental health therapist and consultant, she provides mental health consultation services to organizations on providing effective services to the Black community. [email protected]