Learning Joy and Resilience Through Kindergartners

You are here

Introduction to the Article | Barbara Henderson, Voices Editor

This narrative essay by kindergarten teacher Larissa Hsia-Wong captures many elements of the difficult year-and-half we have all weathered. Her kindergartners, whose normal curriculum would revolve around play and physical interaction with each other and with shared objects, are instead trapped in boxes marked by painter’s tape and pushed ever more strongly to engage in academic-looking tasks that they work on in relative isolation. She reflects on how despite the virus, she sought to make spring 2021 a normal semester for the children, full of joy and playfulness, as they gathered together physically once again. At the same time, the heart of her story addresses the racial reckoning our nation and our local communities are facing.

About the Author

Barbara Henderson, PhD, is the director of the Doctoral Program in Educational Leadership at San Francisco State University and professor in elementary education with an early childhood specialization. Her research expertise is in practitioner and teacher research. She is one of the founding editors of Voices of Practitioners. [email protected]

“Hi, Love Bug. What are you working on today?” I asked one of my kindergarten children during our writing workshop block on poetry. It was a foggy spring morning in San Francisco, and the open windows in our classroom brought in a chilly breeze that along with our classroom fans and COVID-19-compliant air purifier had us all bundled up in coats and beanies.

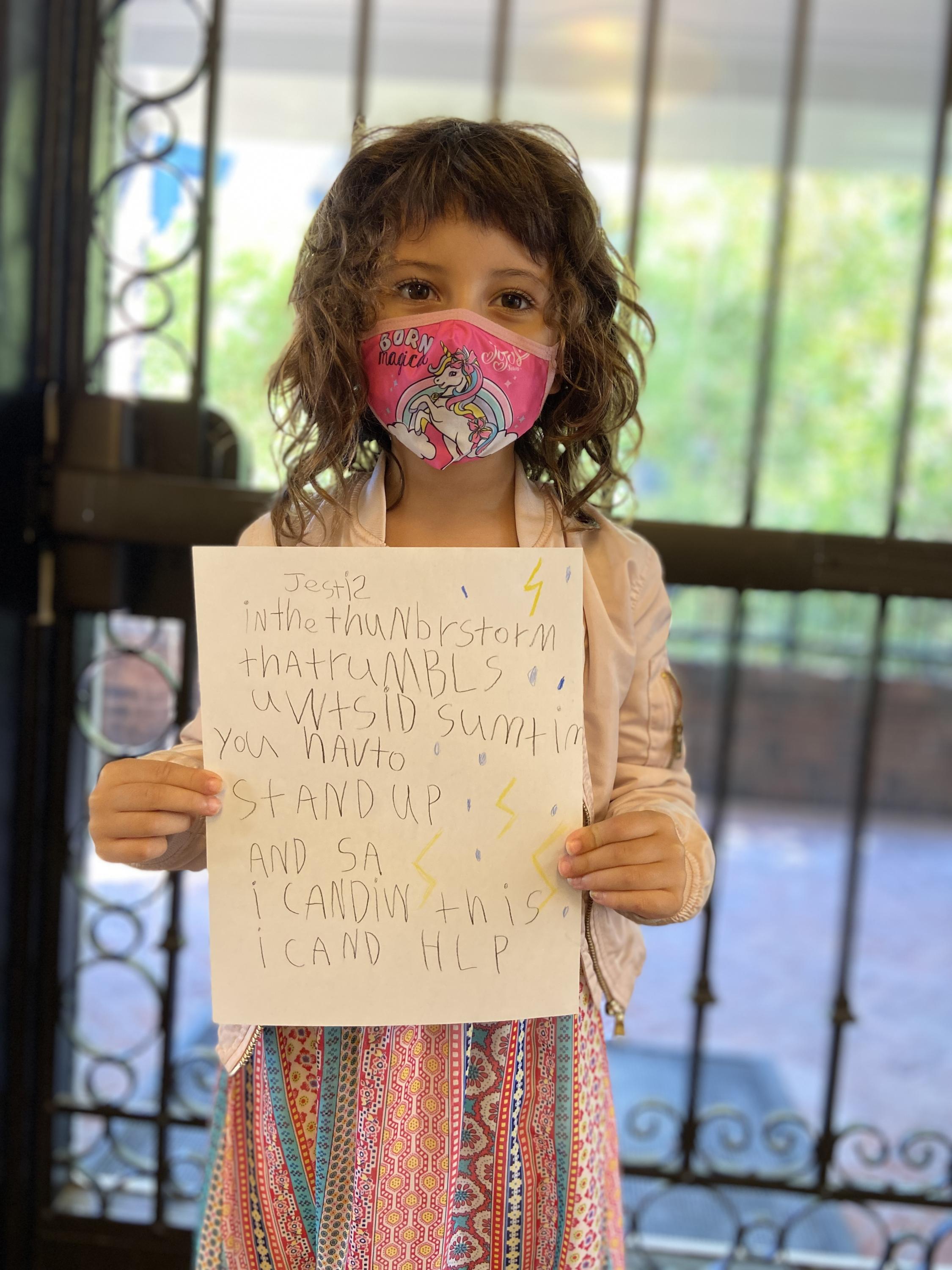

My student was sprawled out on the floor under her individual desk. She was lying on her tummy, her feet kicked up behind her, drawing as she propped herself up on her elbows. Her writing workshop folder was at her side, and scattered around her were colored markers threatening to roll beyond the blue painter’s tape that marked her COVID-19 safe-learning zone. In front of her was a piece of paper covered with the lightning bolts and raindrops she was drawing.

As I knelt down on the floor next to her, she tapped the eraser end of her pencil on the cheek of her face mask (decorated with unicorns, her favorite animals). The straps had trapped a few strands of her brown, wavy hair. She turned her head toward me and said with a twinkle in her eye, “I’m writing a poem about justice!”

“Ooh!” I exclaimed. My mind jumped into action as I silently started to prepare how to re-explain or redefine the complex concept we had been tackling throughout the year.

“Ya! I’m drawing what justice feels like, and you know what?” she asked, her eyes widening as she looked at me expectantly.

“What?” I replied, dutifully.

“It’s like when there’s a scary thunderstorm outside, and then you’re brave and decide to stand up and stop being afraid of it!” she said proudly. She returned to her drawing and began adding a few more raindrops around the lightning bolts.

At that moment, it was all I could do to keep from scooping her into my arms and hugging her. While my brain had gone into overdrive, preparing to jump in and stumble through a re-explanation of what justice means and connecting it to the Black Lives Matter movement and the rise in Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) hate we had recently discussed, my student once again proved to me that our children are profoundly aware and capable of so much when we adults stop projecting our fears and underestimating their understanding of the world.

At that moment, it was all I could do to keep from scooping her into my arms and hugging her. While my brain had gone into overdrive, preparing to jump in and stumble through a re-explanation of what justice means and connecting it to the Black Lives Matter movement and the rise in Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) hate we had recently discussed, my student once again proved to me that our children are profoundly aware and capable of so much when we adults stop projecting our fears and underestimating their understanding of the world.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t hug my student to show how moved by and proud of her I was. The numerous COVID-19 safety protocols our school adopted advised against that. The square marked by blue painter’s tape on the ground indicating her learning zone was a stark reminder of how much the COVID-19 pandemic had transformed our physical learning space and how these physical limitations affected how I felt I could teach. While I was grateful for the opportunity to teach in person, my heart broke every time I looked around at my children’s individual desks six feet apart from each another and when I had to offer an air-hug or air-high-five instead of a real one. When I thought about the toys and imaginative play materials packed up in boxes, the caution tape surrounding the play structure in our playground to prevent children from using it, and the absence of song and dance from our daily routines, I’d shake my head and mutter to myself, “This is not what kindergarten should be like. Where is the joy and magic?”

Teaching during a pandemic is far from magical. Amidst an uncertain background of ever-changing health guidelines, I found myself adopting a crisis mode of teaching and defaulting to a need to control everything. These feelings only intensified as we as a nation and society reckoned with a convergence of crises that challenged our collective and individual capacities to persist, care, empathize, listen, learn, and hope. From the Black Lives Matter protests sparked by the senseless murder of George Floyd to a turbulent and divisive election year to the rise in AAPI hate crimes, I felt my teacher soul and my personal soul drowning in an ever-deepening sea of unanswered questions. These ranged from the logistical (Should I sanitize the children’s hands before we line up for recess or when we get to the recess yard?) to the instructional (How can I teach the /th/ digraph without lowering my mask?) to the pedagogical (How can I modify our writing workshop mini lessons to be grounded in anti-racist pedagogy?) to the personal (Have I, as a Chinese American woman and educator, been complicit in my own erasure all these years?).

And yet, if I took the time to step away from the thunderstorm of doubts, anxieties, stresses, and fears that raged in my own head, I could hear my children happily chatting with one another while they worked, their toes lined up against the blue tape that marked their zones as they peered over to compliment their classmates’ work. If I took the time to stop obsessing over the latest COVID-19 data, I could learn the new, socially distanced tag game my children had invented for recess that brought shrieks of delight from them. If I paused from anxiously monitoring my students during snack time to make sure no one was talking while their masks were off, I could appreciate how they were all waving and grinning at one another silently while they munched on their food. If I took a step back during a community circle, stopped worrying about how to formulate the perfect answer, and let my children talk more, I could learn from their wisdom, empathy, and humor.

As we enter our third school year marked by COVID-19, it can be easy to fall prey to a mounting set of worries and fears and succumb to an untenable need to control everything. However, if we learn to let go a little bit, we can be reminded that our children are incredibly resilient, adaptive, and resourceful. We may not be able to control the spread of the virus, the changing mandates, or the inequities and social justice issues intensified by the pandemic, but we can control how much our children feel loved by us. When our children feel loved, that’s when their magic shines through.

And so, while I may not have been able to give my student a bear hug to communicate everything I couldn’t put into words, I did say, “Love Bug, that is exactly what justice feels like. I never would have thought of it like that! I am so proud of you! Can I give you an air hug?”

“Nope,” my student said with a mischievous grin under her mask. “You can give me a hundred air hugs!”

Justice

Justice

In the thunderstorm

That rumbles outside

Sometimes you just have to

Stand up

And say

“I can do this.

I can help.”

By Jem, 6 years old

Larissa Hsia-Wong, MEd, is the lead kindergarten teacher at Presidio Hill School, a coeducational transitional kindergarden-through-grade-8 independent day school in San Francisco, California. With a background in lower elementary education and English language learner(s), Larissa has served as an elementary school educator, academic language specialist, teacher trainer, and administrator. Larissa is also a doctoral candidate at San Francisco State University. [email protected]