Growing in STEM: STEM Resources and Materials for Engaging Learning Experiences

You are here

Early STEM experiences should include exploratory learning, allowing children to learn content through the processes of inquiry. The STEM experiences teachers provide for young children can involve a variety of learning materials, including children’s literature, consumables and manipulatives, and web-based resources. In this issue we offer suggestions and examples to guide teachers’ selection of classroom STEM resources and materials.

Children’s literature and STEM learning

Use of high-quality STEM-focused children’s literature supports introducing and examining science, technology, engineering, and mathematics concepts in the early childhood classroom (Hong 1996; Patrick, Mantzicopoulos, & Samarapungavan 2008; Sharkawy 2012; Varelas et al. 2014). With the amount of children’s literature aimed at building concept knowledge, teachers may find it difficult to select appropriate books to introduce these ideas. Children’s picture books may contain information that is so oversimplified it can become misleading (Dagher & Ford 2005), leave out key scientific components (Smolkin et al. 2008), or contain little representation of practical or natural sciences (Ford 2005). In addition, finding literature that represents the physical sciences (like motion or astronomy) can be much harder than locating books on life sciences (plants or animals) (Ford 2005; Smolkin et.al. 2008). The difficulties in finding high-quality literature can be intensified when seeking literature about technology, engineering, and mathematics.

In addition to selecting books with high-quality artwork/pictures and text, below are two essential questions to consider before introducing STEM-focused children’s literature into the classroom:

- Does the book present content that is technically sound and appropriate for children’s developing understandings?

- Does the book effectively help students build both inquiry and content understandings?

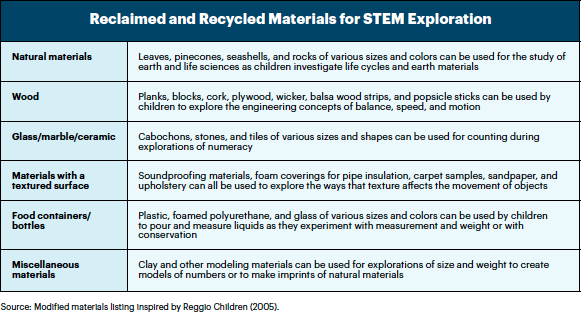

Add loose parts and nonstandard materials for STEM explorations

Another important factor to consider when planningearly STEM experiences is the role open-ended materials can play in classroom learning experiences. STEM experiences often involve many different materials for exploration, but you do not need to purchase manufactured curricular materials. Giving children access to open-ended materials can broaden and extend children’s explorations while also limiting expenditures. Consider the theory of loose parts first proposed by architect Simon Nicholson in the 1970s. Loose parts are materials without a predetermined purpose that can be moved, combined, reformed, taken apart, and put back together in numerous ways(Nicholson 1972). Loose parts can be used alone or combined with other materials and can be both manufactured and natural. Nicholson wrote, “In any environment, both the degree of inventiveness and creativity, and the possibility of discovery, are directly proportional to the number and kind of variables in it” (1972,6). Expanding children’s access to nontraditional STEM materials can serve to provide a wider range of learning opportunities in the classroom.

Consider Remida, the reclaimed materials center in Reggio Emilia, Italy, that houses a wide variety of loose parts and unique items for teachers to bring into their classrooms. This center can serve as a guide for teachers as they build a classroom collection of loose parts for use in STEM explorations.

In order to guide the selection of materials for inclusion in the classroom, think about the following essential questions:

- Can this material be added into a STEM experience or learning center to support student thinking?

- Does the material allow for exploration and inquiry?

- In what ways might children use it to explore the topic at hand?

- How does the material complement the items the children are familiar with?

Examples of High-Quality Children's Books

Life sciences. Looking Closely in the Rain Forest, by Frank Serafini. All ages.

Frank Serafini has a wonderful series of books called Looking Closely. ... This book, focusing on the rain forest, won the National Science Teachers Association’s (NSTA) Outstanding Science Trade Book (OSTB) award in 2011. The writing is almost poetic in its repetition but remains simple and clear enough for very young children to understand. All the books in this series introduce students to the notion of hypothesizing through close inspection, as each plant or animal is preceded by a close-up partial image and the text poses questions about what it might be.

P hysical sciences.I Fall Down, by Vicki Cobb. Ages 3–6.

hysical sciences.I Fall Down, by Vicki Cobb. Ages 3–6.

Vicki Cobb introduces the potentially difficult concept of gravity through easy-to-understand language and activities for young children. This NSTA 2005 OSTB award winner challenges children to drip, dribble, and drop different materials while experimenting with the forces of gravity. Other books in Cobb’s Science Play series include I See Myself (light and reflection), I Get Wet (properties of water), and I Face the Wind (properties of air and air currents).

Technology. Ada Lovelace, Poet of Science: The First Computer Programmer, by Diane Stanley. Ages 4–8.

This is the story of Ada Lovelace, the daughter of Lord and Lady Byron. Credited for having her mother’s mathematical and scientific brain, coupled with her father’s creative imagination, Ada Lovelace was the first recognized computer programmer in history. The text offers insight into the history of computers, the Industrial Revolution, and the mechanical loom. Teachers and librarians can draw connections to history and other forms of technology.

Engineering.The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind (picture book edition), by William Kamkwamba and Bryan Mealer. Ages 5 and up.

Engineering.The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind (picture book edition), by William Kamkwamba and Bryan Mealer. Ages 5 and up.

This book is based on the inspirational, award-winning memoir of 14-year-old William Kamkwamba, who built a windmill from scrap materials to produce electricity for his African village during a drought and famine. This true story about ingenuity, creativity, and persistence in the face of severe adversity will inspire children to imagine their own capabilities. An NSTA OSTB winner in 2012. (There are several books published with this title, so be sure to select the picture book edition.)

Mathematics (numbers and counting). Lifetime: The Amazing Numbers in Animal Lives, by Lola M. Schaefer. All ages.

Winner of NSTA’s OSTB in 2013, Lifetime is filled with charming mixed-media illustrations in numerically accurate pictures. Readers can count how many times a spider spins an egg sac (one) or how many baby seahorses a father seahorse carries in a lifetime (1,000). While younger children may not be able to count to the higher numbers, they can conjecture about more and less, and the text and visual representations make it suitable for even very young audiences. This book also allows for incorporation of science concepts such as life spans and life cycles.

Mathematics (measurement). How Tall, How Short, How Far Away?,

Mathematics (measurement). How Tall, How Short, How Far Away?,

by David A. Adler. Ages 5 and up.

Adler delves into the history of measurement and encourages practical applications for students. This book, which won NSTA’s OSTB award in 1999, encourages readers to learn about and try ancient methods of measurement, as well as design their own tools to measure height and distance.

High-quality STEM web resources

While there are a lot of STEM-related resources available, here are three free tools we think early childhood teachers should know about.

PBS Kids (supports all STEM learning)

PBS Kids provides educational programs, resources for parents and teachers, and a thorough list of STEM games for children ages 2–8. Resources are built around all STEM subjects and encourage students to problem solve through activities that include characters from PBS’s televised programs. www.pbskids.org

Peep and the Big Wide World (science, mathematics, and engineering)

A clever and endearing look into science through the lens of a large urban park, Peep and the Big Wide World is an animated series aimed at 3- to 5-year-olds that can captivate viewers of all ages. Peep introduces children to easy-to-replicate science experiments using everydaymaterials. Renowned early childhood science educator Karen Worth is the show’s educational science advisor, and actress Joan Cusack narrates. The website includes videos, student experiments, and computer activities. www.peepandthebigwideworld.com/en/

Code.org (technology)

This nonprofit organization is dedicated to teaching K–12 students how to code. While all students can benefit, a primary goal of Code.org is to provide technology opportunities to females and other students underrepresented in the computer science field. Videos explain what coding is, and users can access early childhood activities and lesson plans after creating a free account. https://code.org/

Conclusion

We hope early childhood teachers are inspired to think creatively as they plan STEM integration. Teachers can support children’s exploration and learning by ensuring that they have many opportunities for playful engagement. Diversifying STEM materials and resources to include both traditional and nontraditional tools, high-quality STEM literature, and web-based resources deepens children’s daily engagement in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

References

Dagher, Z.R., & D.J. Ford. 2005. “How Are Scientists Portrayed in Children’s Science Biographies?” Science & Education 14 (3): 377–93.

Ford, D.J. 2005. “Representations of Science Within Children’s Trade Books.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 43 (2): 214–35.

Hong, H. 1996. “Effects of Mathematics Learning Through Children’s Literature on Math Achievement and Dispositional Outcomes.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 11 (4): 477–94.

Nicholson, S. 1972. “The Theory of Loose Parts: An Important Principle for Design Methodology.” Studies in Design Education Craft and Technology 4(2): 5–14.

NSTA (National Science Teachers Association). 2016. NSTA Recommends. www.nsta.org/recommends/.

Patrick, H., P. Mantzicopoulos, & A. Samarapungavan. 2008. “Motivation for Learning Science in Kindergarten: Is There a Gender Gap and Does Integrated Inquiry and Literacy Instruction Make a Difference.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 46 (2): 166–91.

Reggio Children. 2005. Remida Day. Reggio Emilia, Italy: Reggio Children.

Sharkawy, A. 2012. “Exploring the Potential of Using Stories About Diverse Scientists and Reflective Activities to Enrich Primary Students’ Images of Scientists and Scientific Work.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 7 (2):307–40.

Smolkin, L.B., E.M. McTigue, C.A. Donovan, & J.M. Coleman. 2008. “Explanation in Science Trade Books Recommended for Use With Elementary Students.” Science Education 93 (4): 587–610.

Varelas, M., L. Pieper, A. Arsenault, C.C. Pappas, & N. Keblawe-Shamah. 2014. “How Science Texts and Hands-On Explorations Facilitate Meaning Making: Learning From Latina/o Third Graders.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 51 (10): 1246–74.

Bree Laverdiere Ruzzi is a PhD student and graduate teacher assistant at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia. Bree was previously a K–12 school librarian for Virginia Beach City Public Schools. Her research includes working with school librarians and early childhood/elementary teachers to collaboratively create inquiry-based science instruction enjoyable to young students. [email protected]

Angela Eckhoff, PhD, is an associate professor of teaching and learning–early childhood at Old Dominion University, in Norfolk, Virginia.