Modeling Curiosity and Acceptance: My Kindergarten Lunch Story

When I began kindergarten, I knew I was different from most of my peers, but it became particularly evident to me during lunchtime on the first days of school. I knew my mother had taken great care to pack my favorites for lunch—rice (bap), some pickled radish (danmuji), marinated cooked beef (bulgogi). As I watched my classmates unwrap their peanut butter sandwiches and their cheese and crackers, I could see their reactions. The odors of my lunch were so different from what the other children were used to, and more than one of my classmates let me know they thought my lunch smelled weird. After seeing the reactions of my classmates, I didn’t want to eat my favorite dishes at school.

My lunch highlighted for me that I wasn’t like most of my classmates. I didn’t want to feel excluded. It felt easiest to just pretend I wasn’t hungry at lunchtime and then eat later, after school ended, without the looks and comments.

However, my teacher noticed that I wasn’t eating at lunchtime. She understood why right away. So during lunchtime, she asked me to share what I had brought for lunch and asked a few questions while drawing connections to the experiences of my peers. My classmates became curious and also asked questions. They wondered about the color of the radish (it’s bright yellow). They thought the rice being sticky could make it easier to eat than the rice many of them were used to. As my teacher modeled curiosity and acceptance, my differences started to feel interesting and okay to talk about instead of excluding. Looking back, I’m thankful that one of my first teachers worked to understand how I might feel excluded and asked questions and modeled to my classmates how to make me feel more welcomed.

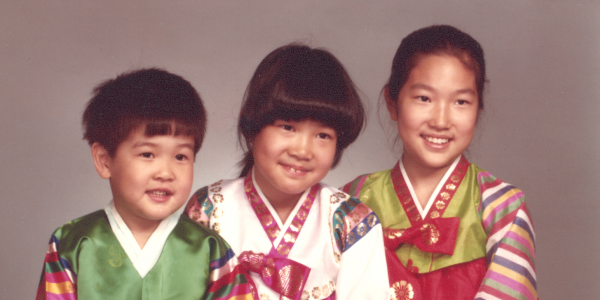

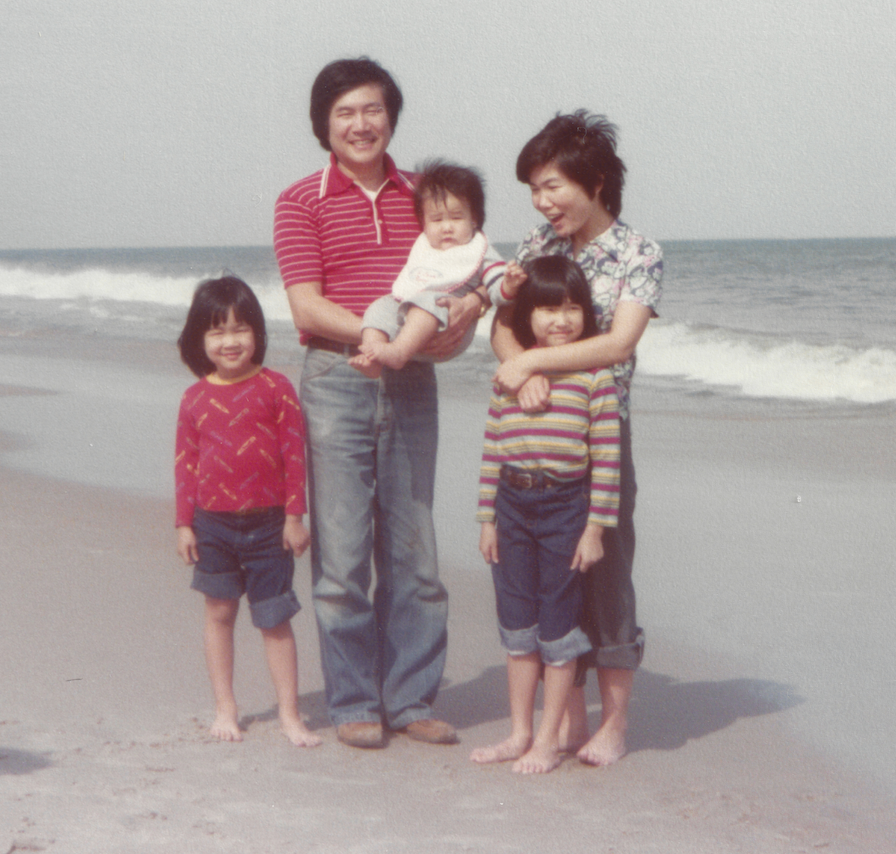

As Asian American Pacific Islander Month comes to a close, I’ve been reflecting on my own experience as the daughter of Korean immigrants. Asian American Pacific Islander is a broad term encompassing many cultures and stories. Like other Asian American Pacific Islander families, my family has our own story, grounded in our specific culture and experiences. My story is one of both feeling different from others in Fredericksburg, Virginia, where I grew up and also appreciative of those who grew to know and include me.

My father came to America with a single suitcase of belongings and $200 in pursuit of greater opportunities than what he saw for himself and his family in Korea. After my mother finished nursing school, she joined my father. Together, they started a family and a life in the US where the language and culture were at times difficult for them to understand. They navigated the challenges of establishing careers and parenting children in a community where there were few other Asian families and their own families were far away. As a parent now, I can hardly fathom taking on these challenges amidst language barriers and without the physical support of family and close friends. My parents embodied courage, resilience, and kindness in a way that I try to emulate in my own life now.

But my story is not the only one that sounds like this. Others have had similar journeys, and many of these stories are present within our field. Consider the teachers who are parents who left their native countries; the program leaders who are children of immigrants; the children for whom English is a second language; the parents who are trying to understand what is best for young children in a school culture different from their home culture and who are looking for support and help. With the backdrop of these unique stories of educators and families, early childhood programs can be deeply impactful places for young children. Sometimes they can be places where children and families feel excluded. Fortunately for me, one of my first teachers modeled support and understanding, working to bridge home and school and to welcome me and my family.

I know my experience is not unusual. There are educators who teach and model curiosity, kindness, and acceptance for children with all their differences every day. We see this in the programs we visit for accreditation, and we hear these stories when we talk with educators caring for families in our member advocacy. I have great confidence that there are many programs that provide a supportive and inclusive environment where a child can eat their (native) lunch and feel accepted. I am deeply grateful to be part of a field that provides inclusive and welcoming places for educators, children, and families every day.

How To Build Empathy in Your Classroom

Modeling and teaching empathy—concern for others’ feelings—is an important part of being an effective, culturally competent teacher. The following tips can help you consider your assumptions, expectations, and biases so that you can better develop your own empathy and the children’s as well.

- Think about it. When teachers have unfavorable perceptions about children who differ from them (in terms of culture, race, or ethnic identity), children’s learning is negatively impacted.

- Make a difference. Commit to self-reflection to uncover your personal biases and assumptions. Help bridge understanding across cultural groups.

- Ask yourself hard questions. Reflect on questions like: What are my initial reactions to this child and her family? What do those reactions tell me about my personal beliefs and assumptions? What can I do to build children’s and families’ trust? How can I connect with them in meaningful ways?

- Model warm and responsive actions. Greet children with a smile and welcoming words. Anticipate and promptly address children’s needs and worries.

- Highlight respect, kindness, compassion, and responsibility throughout your classroom. Carefully select books, games, music, and other materials for your lessons and activities. Help children discover similarities with peers from different backgrounds.

- Build a classroom library that features diversity. Make sure the books include characters who reflect the many different identities of the children in your classroom. It’s important for all children—and particularly those of color—to see themselves in stories.

- Invite guests to share their cultures, traditions, and talents. Tap into children’s and families’ interests and cultural resources by creating time and space for them to share their special skills and knowledge in the classroom.

- Acknowledge your progress. Consider the changes you’re making and honor your journey. You are becoming a more culturally competent teacher who is deeply empathetic toward all the children in your class.

—Susan Friedman, Senior Director, Publishing & Content Development

This article was published as an 8x. “Developing Empathy to Build Warm, Inclusive Classrooms” by Susan Friedman in the April/May 2019 issue of Teaching Young Children. You can read the full issue at NAEYC.org/tyc/apr2019.

Recommended Resources

- NAEYC Asian Interest Forum. https://www.naeyc.org/get-involved/communities/how-join-interest-forum.

- “Advancing Equity In Early Childhood Education” position statement. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity.

- Families and Educators Together: Building Great Relationships that Support Young Children, by Derry Koralek, Karen Nemeth, and Kelly Ramsey (2019).

- Each and Every Child: Using an Equity Lens When Teaching in Preschool, by Susan Friedman and Alissa Mwenelupembe (2020).

- “Valuing Diversity: Developing a Deeper Understanding of All Children’s Behavior,” by Barbara Kaiser and Judy Sklar Rasminsky. In the December 2019/January 2020 issue of Teaching Young Children.

- “Diverse Children, Uniform Standards: Using Early Learning and Development Standards in Multicultural Classrooms,” by Jeanne L. Reid, Catherine Scott-Little, and Sharon Lynn Kagan. In the November 2019 issue of Young Children.

Michelle Kang serves as NAEYC’s Chief Executive Officer.