Teaching Emotional Intelligence in Early Childhood

You are here

Every morning, Ms. Mitchell thinks about how her feelings will affect her teaching. If she feels frustrated or overwhelmed when she arrives at school, she takes a deep breath and makes a plan for managing her emotions so that she can fully engage with her students and coteachers. She greets children and families as they walk through the door and asks how they are feeling. Throughout the day, children use a classroom mood meter to acknowledge their feelings. Ms. Mitchell also uses the mood meter to talk with children about her own feelings, how characters in books feel, what happened to cause their feelings, and how characters’ emotions change throughout a story. In many different ways, Ms. Mitchell models emotional intelligence and supports its development in her students.

Emotional intelligence is a set of skills associated with monitoring one’s own and others’ emotions, and the ability to use emotions to guide one’s thinking and actions (Salovey & Mayer 1990). Emotions impact our attention, memory, and learning; our ability to build relationships with others; and our physical and mental health (Salovey & Mayer 1990). Developing emotional intelligence enables us to manage emotions effectively and avoid being derailed, for example, by a flash of anger.

Children with higher emotional intelligence are better able to pay attention, are more engaged in school, have more positive relationships, and are more empathic.

Emotional intelligence is related to many important outcomes for children and adults. Children with higher emotional intelligence are better able to pay attention, are more engaged in school, have more positive relationships, and are more empathic (Raver, Garner, & Smith-Donald 2007; Eggum et al. 2011). They also regulate their behaviors better and earn higher grades (Rivers et al. 2012). For adults, higher emotional intelligence is linked to better relationships, more positive feelings about work, and, for teachers in particular, lower job-related stress and burnout (Brackett, Rivers, & Salovey 2011).

Drawing from Mayer and Salovey’s (1997) refined theory of emotional intelligence, Brackett and Rivers (2014) identified five skills that can be taught to increase emotional intelligence: Recognizing emotions in oneself and others; Understanding the causes and consequences of emotions; Labeling emotions accurately; Expressing emotions in ways that are appropriate for the time, place, and culture; and Regulating emotions. These skills, which form the acronym RULER, are the heart of an effective approach for modeling emotional intelligence and teaching the emotional intelligence skills children need to be ready to learn (Hagelskamp et al. 2013; Rivers et al. 2013).

While the full RULER approach provides a range of tools and instructional strategies, in this article we focus on the mood meter, which is a color-coded tool that provides a shared language for becoming aware of emotions and their impact on teaching and learning. (To learn about the full RULER model, visit the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence website at http://ei.yale.edu/ruler/.)

Introducing the mood meter

If you ask a group of 3-year-old children how they are feeling, what would they say? Fine? Good? Happy? What if you ask a group of early childhood educators? Their responses might not be that different! Most of us use a limited vocabulary to describe our feelings when answering the question “How are you?” In contrast, schools that value children’s and educators’ emotions encourage a diversified vocabulary to describe feelings. The mood meter is a concrete tool that can shift conversations about feelings from rote responses like good to more nuanced responses like curious, excited, or worried. Accurately labeling and discussing feelings helps adults and children acknowledge the role that emotions play throughout the day. Taking time to recognize feelings, elaborate on their causes, and jointly brainstorm potential strategies to shift or maintain them helps ensure that adults and children use emotions effectively to create a climate supportive of learning.

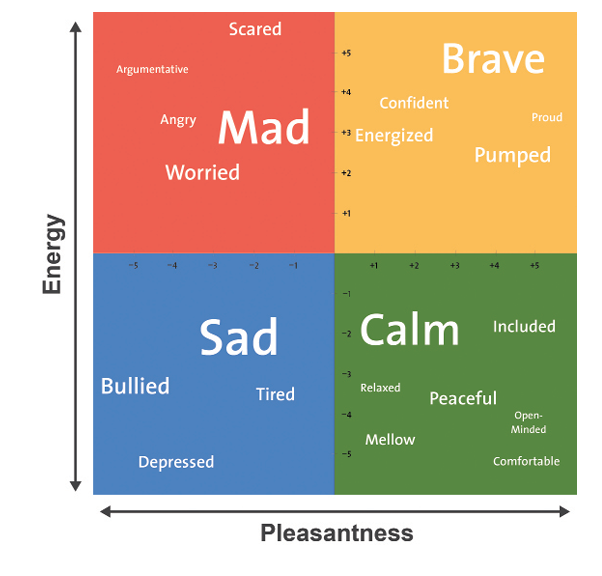

The mood meter has two axes. The horizontal axis represents pleasantness and ranges from -5 (on the far left) to +5 (on the far right), with -5 being the least pleasant you can imagine feeling (e.g., your job is at risk) and +5 being the most pleasant you can imagine feeling (e.g., you were recognized as Teacher of the Year). Our feelings usually fall somewhere between these values. The vertical axis, which has the same range, represents the energy we experience in our bodies (e.g., heart rate, breathing). At -5, you might feel drained of all energy (e.g., you have the flu and can hardly move) while +5 represents feeling the most energy you can imagine having in your body (e.g., you just received a big raise and feel like jumping for joy). Together, the two axes create four colored quadrants (from the top left and counterclockwise) red (unpleasant, higher energy), blue (unpleasant, lower energy), green (pleasant, lower energy), and yellow (pleasant, higher energy).

With young children ages 3 to 8, a simplified color-only version of the mood meter works best, in our experience. When first introducing children to the mood meter, we tend to describe each color with one word: red = angry; blue = sad; green = calm; yellow = happy. As children learn to use the mood meter, they acquire more feeling words that correspond to each color (and in later grades, they learn how to use the numeric ranges to express their degree of pleasantness and energy). With the mood meter, children learn that there are no good or bad feelings. There may be feelings that we like to have more often than others, but all feelings are okay. Even for those unpleasant feelings, we can learn to employ strategies that use the information we receive from our feelings to respond to them in ways we feel good about.

Using the mood meter to practice emotional intelligence

Research suggests that an important part of effectively teaching emotional intelligence is modeling the five RULER skills for children (Jennings & Greenberg 2009). One way to do this is by regularly checking in on the mood meter throughout the day.

Recognize: How am I feeling? Cues from our bodies (e.g., posture, energy level, breathing, and heart rate) can help us identify our levels of pleasantness and energy. Think about how our feelings may affect the interactions we have with others.

Understand: What happened that led me to feel this way? As feelings change throughout the day, think about the possible causes of these feelings. Identifying the things (e.g., people, thoughts, and events) that lead to uncomfortable feelings can help us both manage and anticipate them in order to prepare an effective response. Determining the causes of feelings we want to foster can help us consciously embrace those things for ourselves and others more often.

Label: What word best describes how I am feeling? Although there are more than 2,000 emotion words in the English language, most of us use a very limited number of words to describe how we are feeling (e.g., happy, sad, mad). Cultivating a rich vocabulary allows us to pinpoint our emotions accurately, communicate effectively, and identify appropriate regulation strategies.

Express: How can I express appropriately what I am feeling for this time and place? There are many ways to express each of our feelings. At different times and in different contexts, some forms of expression are more effective than others. Explaining to children what we are doing and why, as we express different feelings at school, provides them with models of different strategies to express their own emotions.

Regulate: What can I do to maintain my feeling (if I want to continue feeling this way) or shift my feeling (if I do not want to continue feeling this way)? Having short-term strategies to manage emotions in the moment as well as long-term strategies to manage emotions over time is a critical part of effective regulation. Educators with a range of regulation strategies to choose from are better able to manage the full range of emotions and to model these strategies for children and families.

Strategies that can effectively regulate emotions include

- Taking deep breaths

- Engaging in private self-talk (e.g., “I know I can do this!”)

- Reframing negative interactions (e.g., “She is having a hard day. No wonder she reacted that way.”)

- Stepping back and allowing physical distance (e.g., taking a short walk at lunch time)

- Seeking social support (e.g., talking to a friend and making plans to spend time together)

Promoting children’s emotional intelligence skills

How do you want children to feel when they are in your classroom? Most educators respond with emotions like happy, secure, safe, peaceful, and curious—pleasant feelings that are conducive to learning (Reschly et al. 2008). There are exceptions, however. For example, feeling extremely excited (high in the yellow) can make it challenging to concentrate on a quiet task. There are also occasions when unpleasant feelings can be helpful. For example, mild frustration may help a child persevere to complete a challenging task, and some sadness (which is connected to compassion and sympathy) is necessary to develop empathy. While we do not want to foster unpleasant feelings in young children, we do want to provide them with strategies to both accept and manage these feelings when they occur.

In addition to modeling, educators can promote emotional intelligence through direct instruction by embedding the mood meter in classroom management practices as well as formal and informal learning activities. We provide examples of each in the following sections.

Integrating emotional intelligence into classroom management practices

Educators can use their own emotional intelligence to acknowledge the feelings children experience throughout the day and to inform classroom management. For example, by recognizing emotion cues in children, educators can help children connect their physical experience of emotions with new vocabulary on the mood meter (e.g., frustrated, annoyed, calm). A teacher could say, “I see you are frowning and crossing your arms. I do that when I feel frustrated or annoyed. It looks like you might be in the red. How are you feeling? What happened that caused you to feel that way?” Recognizing and discussing emotions with children lays a foundation for their self-regulation. Educators can also use this information to identify when a classroom activity needs to be modified to better engage students. For instance, an activity requiring children to cut a complex shape with scissors may be too challenging, leading children to feel frustrated and require more support. Similarly, adding more materials to a table activity might shift children who are feeling bored (in the blue) to feeling interested (yellow). Using music and movement during group time might shift children who are feeling excited (yellow) to feeling relaxed (green) after they release their energy appropriately. If students are experiencing separation anxiety (blue) in the mornings, for instance, educators can use role-play at circle time to explore how children can help a friend who is feeling lonely. Children can then practice empathy by supporting one another.

Supporting emotional intelligence through read-alouds

Educators can help children expand their knowledge of feelings with carefully selected read-alouds. Teachers can use read-alouds to introduce children to new vocabulary for expressing emotions and then relate the feelings in stories to classroom themes. For example, words like nervous or brave fit well with a theme focused on visiting the doctor’s office. When introducing a new feeling word, consider providing children with developmentally appropriate definitions of the word (e.g., “Disappointed means feeling sad because something did not happen the way you wanted it to.”) and pairing the new word with related familiar words (e.g., “Disappointed is a blue feeling, like sad.”). Using the mood meter during read-alouds helps children consider the emotions of storybook characters and practice applying their emotional intelligence. Photocopies of pictures from books can be placed on the mood meter and moved around as their feelings change throughout the story. Thinking through how characters feel and react helps children better prepare to deal with their own range of emotions and behaviors.

Developing emotional intelligence enables us to manage emotions effectively and avoid being derailed, for example, by a flash of anger.

The RULER acronym can guide educators in their discussions with children about each new feeling word. For example, using book characters, educators can help children understand what a feeling looks like (recognizing and labeling), different things that cause feelings in themselves and others (understanding), and appropriate ways to show their feelings at school as well as how to shift or maintain that feeling (expressing and regulating). Use the questions in the table “Sample Read-Aloud Questions” to help children explore feelings during shared reading and guide conversations with children throughout the day.

Sample Read-Aloud Questions

Recognize: How is the character feeling? How do you know he/she is feeling that way? Can you show me a _________________ face?

Understand: What happened that made the character feel _________________ ? What happens that makes you feel _________________ ?

Label: Where would you put this character on the mood meter? What is the name of this feeling?

Express: How did the character act when he/she was feeling _________________ ? What else can you do when you are feeling _________________ ?

Regulate: What did the character do when he/she felt _________________ ? What could you do to help a friend who is feeling _________________ ? When you feel _________________ , what do you do?

Sharing personal stories about emotions

Another way teachers can embed emotional intelligence in the classroom routine is by sharing stories about their own feelings. Hearing about the emotional experiences of others helps children understand helpful ways to express and regulate emotions. Educators can share short (2–3 minute) developmentally appropriate stories during morning meeting, large or small group time, or snacks or meals. If educators describe how the emotion looked and felt, the situation that caused the emotion, and how they expressed and regulated the emotion, they will foster a classroom environment where children feel supported sharing their own emotions. Here is an example of an appropriate personal story to relate:

I remember a time when I was your age and I felt scared. I was afraid of my neighbors’ dog. Whenever I walked by their house, the dog would bark. My eyes would get wide like this, I could feel my shoulders tensing up like this, and then I would run past their house as fast as I could. Sometimes I even had bad dreams about the dog chasing me, so I decided to tell my mom about it. Talking to someone is one thing you can do when you feel scared. My mom gave me a big hug, and that helped me feel better. She told me she had met the neighbors’ dog, and his name was Jack! She said he was very friendly and took me to meet him. I didn’t want to pet him at first, but then I touched his tail. Our neighbor said that barking was just Jack’s way of saying hello. After that, I didn’t feel so afraid of him anymore.

I remember a time when I was your age and I felt scared. I was afraid of my neighbors’ dog. Whenever I walked by their house, the dog would bark. My eyes would get wide like this, I could feel my shoulders tensing up like this, and then I would run past their house as fast as I could. Sometimes I even had bad dreams about the dog chasing me, so I decided to tell my mom about it. Talking to someone is one thing you can do when you feel scared. My mom gave me a big hug, and that helped me feel better. She told me she had met the neighbors’ dog, and his name was Jack! She said he was very friendly and took me to meet him. I didn’t want to pet him at first, but then I touched his tail. Our neighbor said that barking was just Jack’s way of saying hello. After that, I didn’t feel so afraid of him anymore.

Of course, the goal of sharing a story isn’t merely for children to listen. The teacher’s personal stories should be discussed (much like a read-aloud), and children should be invited to share their stories about times they felt that emotion and what they did as well.

Encouraging children to place their name or picture on the corresponding mood-meter color can help children think about how they are feeling, why, and how to appropriately express and regulate their feelings.

Extending emotional intelligence throughout the day

Educators can help children develop RULER skills by integrating them into a range of activities, including creative arts, music and movement, and more. Here are a few examples:

- Integrate green feelings (pleasant and lower energy) into creative arts by having children paint calmly and slowly while taking deep breaths and listening to soft music.

- Invite children to practice feeling yellow (pleasant and higher energy) by dancing to fast music. After they’ve been dancing long enough for their heart rates to quicken, have children place their hands on their chests to feel their hearts beating, and talk about heartbeats as one way we can feel the energy in our bodies. (For a math extension, the teacher can also measure the resting and dancing heart rates of a few children, then create a chart with the class.)

- Use pretend play to help children practice appropriately expressing red and blue emotions. Teachers can guide children’s responses to pretend scenarios and model appropriate language and emotional expression.

- Integrate mood meter check-ins into classroom routines (e.g., when children arrive and during group time). Encouraging children to place their name or picture on the corresponding mood-meter color can help children think about how they are feeling, why, and how to appropriately express and regulate their feelings.

Conclusion

Along with teaching the RULER skills and embedding the mood meter in classroom practices, educators should take time to discuss with colleagues the most helpful ways for children to express emotions in the classroom, especially unpleasant emotions. How can a child effectively express anger in your classroom? Is it okay for a child to verbalize “I’m angry?” Probably. Is it okay for a child to push another child? Probably not. Having these discussions among educators, as well as engaging parents, is critical to developing a set of school norms on emotions and effectively teaching these norms to children. Take time to share the mood meter with families. Let them know how you use the mood meter at school, and offer strategies that help them talk with their children—and each other—about emotions at home. By taking these simple steps, we can boost children’s emotional intelligence, helping them positively engage in school and in life.

References

Brackett, M.A., & S.E. Rivers. 2014. “Transforming Students’ Lives With Social and Emotional Learning.” In International Handbook of Emotions in Education, eds. R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia, 368–88. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Brackett, M.A., S.E. Rivers, & P. Salovey. 2011. “Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Personal, Social, Academic, and Workplace Success.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 5 (1): 88–103.

Eggum, N.D., N. Eisenberg, K. Kao, T.L. Spinrad, R. Bolnick, C. Hofer, A.S. Kupfer, & W.V. Fabricius. 2011. “Emotion Understanding, Theory of Mind, and Prosocial Orientation: Relations Over Time in Early Childhood.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 6 (1): 4–16.

Hagelskamp, C., M.A. Brackett, S.E. Rivers, & P. Salovey. 2013. “Improving Classroom Quality With the RULER Approach to Social and Emotional Learning: Proximal and Distal Outcomes.” American Journal of Community Psychology 51 (3–4): 530–43.

Jennings, P.A., & M.T. Greenberg. 2009. “The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher Social and Emotional Competence in Relation to Student and Classroom Outcomes.” Review of Educational Research 79 (1): 491–525.

Mayer, J.D., & P. Salovey 1997. “What Is Emotional Intelligence?” In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational Implications, eds. P. Salovey & D.J. Sluyter, 3–31. New York: Basic Books.

Raver, C.C., P.W. Garner, & R. Smith-Donald. 2007. “The Roles of Emotion Regulation and Emotion Knowledge for Children’s Academic Readiness: Are the Links Causal?” In School Readiness and the Transition to Kindergarten in the Era of Accountability, eds. R.C. Pianta, M.J. Cox, & K.L. Snow, 121–47. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Reschly, A.L., E.S. Huebner, J.J. Appleton, & S. Antaramian. 2008. “Engagement as Flourishing: The Contribution of Positive Emotions and Coping to Adolescents’ Engagement at School and With Learning.” Psychology in the Schools 45 (5): 419–31.

Rivers, S.E., M.A. Brackett, M.R. Reyes, J.D. Mayer, D.R. Caruso, & P. Salovey. 2012. “Measuring Emotional Intelligence in Early Adolescence With the MSCEIT-YV: Psychometric Properties and Relationship With Academic Performance and Psychosocial Functioning.” Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 30 (4): 344–66.

Rivers, S.E., S.L. Tominey, E.C. O’Bryon, & M.A. Brackett. 2013. “Developing Emotional Skills in Early Childhood Settings Using Preschool RULER.” The Psychology of Education Review 37 (2): 19–25.

Salovey, P., & J.D. Mayer. 1990. “Emotional Intelligence.” Imagination, Cognition, and Personality 9 (3): 185–211.

Photographs: 1, © Julia Luckenbill; 2, 4, © iStock; 3, 5, courtesy of the author

Shauna L. Tominey, PhD, is an assistant professor of practice and a parenting education specialist at Oregon State University. She previously served as the director of early childhood programming and teacher education at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence. Her research focuses on the development of programs that promote social and emotional skills for children and adults. [email protected]

Elisabeth C. O’Bryon, PhD, is the director of research at GreatSchools, a national nonprofit that helps millions of parents getting great education for their children. She works in the Washington, DC, area and has a background in school psychology.

Susan E. Rivers, PhD, is executive director and chief scientist of iThrive, a nonprofit in Newton, Massachusetts, committed to transforming youth through the power of games. She cofounded the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and is a lead developer of Preschool RULER and the RULER framework for elementary and middle school. [email protected]

Sharon Shapses, MS, is a preschool consultant with RULER and RULER for Families and a coach for the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence. She has served as an early childhood teacher, parent cooperative preschool director, educator, answering the system professor, and instructional coach. [email protected]