Preparing Equitable and Inclusive Early Childhood Educators: Three Evidence-Based Strategies

You are here

Josephina’s head is spinning. As chair of an early childhood program at a community college, she faces many tasks, including documenting how courses are responsive to her campus diversity plan and revising coursework and field experiences to align with both state and national standards. Part of the new definition of developmentally appropriate practice in NAEYC’s most recent position statement gives her pause: “To be developmentally appropriate, practices must also be culturally, linguistically, and ability appropriate for each child.” Realizing that many courses in her program have been taught the same way for years, she wonders how she might engage community partners and faculty to address recent shifts in the field, respond to a changing community context, and prepare students to address issues of equity and inclusion. Where should she start?

Recently, early childhood faculty, researchers, policymakers, and practitioners have intentionally and thoughtfully examined ways the field can implement practices informed by research in developmental science (IMNRC 2015), ensure equitable learning opportunities for and full inclusion of children from all social identities (NAEYC 2019b), and define the early childhood profession as a professional field of practice (Goffin 2015; American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees et al. 2020). Central to each of these interrelated efforts is a focus on ensuring that all early childhood educators have the knowledge, skills, and dispositions to be effective. The goal of this focus is to shift from preparing early childhood educators to support all children to preparing them to support each and every child.

For higher education institutions, this represents an urgent need to deliver coursework and field experiences that prepare an early childhood workforce equipped to embrace the opportunities and demands of a pluralistic and democratic society. Importantly, NAEYC’s recently revised statement on developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) impels institutions of higher education to address their own biases and inequalities and prepare educators who can “provide developmentally, culturally, and linguistically responsive learning experiences to an increasingly diverse population of children” (2020, 4).

The purpose of this article is to describe three effective and evidence-based strategies that are part of the Blueprint process (Catlett, Maude, & Skinner 2016). This article is organized to support readers to learn about and utilize these strategies. Following a description of each strategy, we illustrate how Josephina and her colleagues use it to enhance their early childhood courses and program, with the goal of preparing students to work with children and families in developmentally, culturally, and linguistically responsive ways. We conclude by sharing resources that can help early childhood program faculty deconstruct and reconstruct their syllabi.

The Blueprint Process: A Sequence for Addressing Diversity in Educator Preparation Programs

The original Blueprint process was created by the second author and colleagues to develop a sequence to bring explicit attention to and build emphasis on cultural, linguistic, and ability diversity in coursework, field experiences, and practices in early childhood higher education programs. This was accomplished through an integrated sequence of campus-community values clarification activities, faculty professional development, and enhancements to syllabi and field experiences.

The initial process was developed, field tested, and evaluated, demonstrating the efficacy of this approach in changing both faculty knowledge and course content (Maude et al. 2010). The three basic components of the process were revised in 2011 and then implemented in early childhood higher education programs at community colleges in six states. Additional attention was paid in the revised version to both faculty and student outcomes—both of which have remained consistently positive (Catlett et al. 2014). Currently, multiple higher education early childhood programs across the country are using the Blueprint process to support shifts in preparing early childhood educators that are consistent with diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The Blueprint strategies addressed in this article have been shown to enhance the professional preparation of early childhood educators (Maude et al. 2010). The strategies, in order, include:

- Decide what is important using a collaborative process.

- Measure what you treasure using a syllabus rubric.

- Deconstruct and reconstruct syllabi to ensure alignment, depth, and explicitness in both content and instructional practices.

What Difference Do These Strategies Make?

Research involving higher education programs that have implemented the strategies in this article have highlighted positive changes. These changes include increased faculty willingness to use evidence-based resources and practices on culture, language, and ability diversity and greater use of the new practices by teacher candidates during field experiences (Catlett et al. 2014, 122). Faculty and administrators who are currently implementing these practices have also shared the following observations that they attribute to the Blueprint process.

From the Chair of an Early Childhood Education Program

- Candidates are more reflective and have a better understanding of how their own upbringing affects how they interact with children and families.

- Candidates seem to care more about the assignments because they know they will be able to use them when they enter the field or in their current workplace.

- Personas give candidates a story to connect to, analyze, and reflect on, and they put more effort into assignments because they are not so abstract.

From a Field Experience Supervisor

- Candidates have greater awareness of and ability to individualize instruction for all children.

- Candidates are much more aware of and have the skills to support children who are dual language learners.

- Candidates have an increased knowledge base about inclusion, diversity, partnering with families, and communication.

- The photo and details make the personas real to the candidates and to the extent that they genuinely want to figure out how to support the child and family.

Decide What Is Important: A Collaborative Process

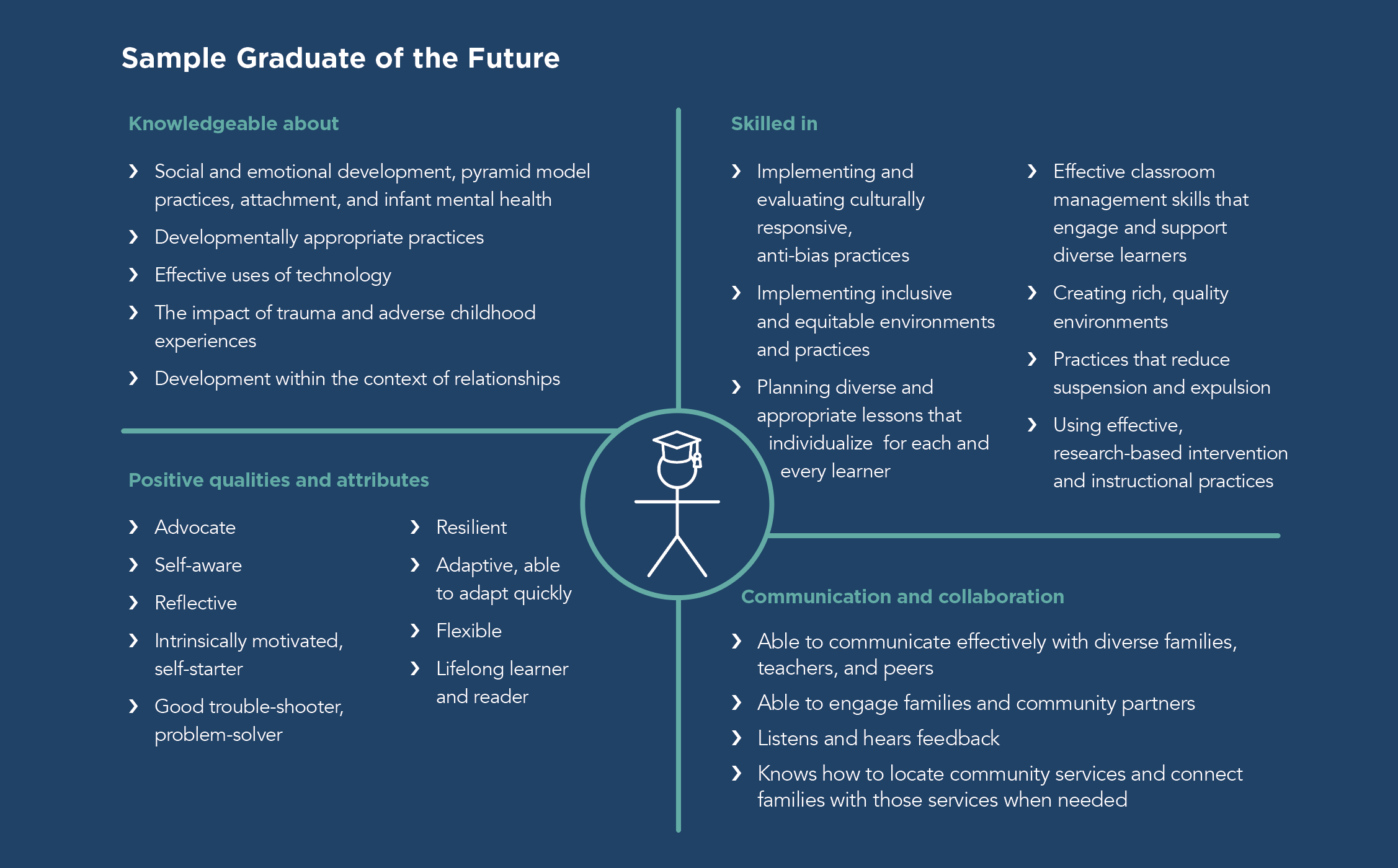

Deciding what is valued by faculty and community partners is the first strategy of the Blueprint process and is foundational to the other two. One way to clarify a program’s values and vision is to have community partners engage in the activity Graduate of the Future (see Sample Graduate of the Future below for a sample end product). During this activity, participants work together to create a picture of what they want future graduates of the early childhood program (and future members of the early childhood workforce) to know and be able to do. Along with program faculty and staff, community partners can include recent graduates, staff from local early childhood programs, representatives from field- and clinical-experience sites, early intervention providers, early childhood mental health providers, and other partners from local schools. The Graduate of the Future activity can also be done virtually. Google’s Jamboard and other digital whiteboard systems support interactive brainstorming.

In the case of Josephina, her community recently experienced an influx of refugee families from Afghanistan, so she also invited members of local ethnically based community organizations that support refugees to provide insights about the capabilities students will need to support new community members. Josephina is delighted that 22 participants have accepted the invitation to participate. She has heard that the number of participants in this initial meeting can vary from 10 to 40 people, depending on the size of the higher education program and the number of partners in the community.

To begin, Josephina labels a sheet of flip chart paper with the words “Graduate of the Future,” then draws a simple figure of a gender-neutral graduate and posts the paper where everyone can see it. Next, she asks everyone to think about the knowledge, skills, and dispositions they think program graduates should have in order to best serve children and families and to write those characteristics on sticky notes. Participants then post the notes on the flip chart paper, creating a visual display of what faculty and community partners value most. The Graduate of the Future activity provides an important springboard for discussion, and participants add additional sticky notes as new ideas are generated. Following the meeting, Josephina transcribes the sticky notes and identifies key themes that reflect what the campus and community partners believe her program’s early childhood graduates should know and be able to do.

In this way, the Graduate of the Future activity provides Josephina and her colleagues with information about ways in which they could enhance coursework, field experiences, and program practices to reflect what they value most.

More specifically, the findings from Josephina’s Graduate of the Future activity highlight the need for coursework to more explicitly emphasize preparing teacher candidates in four areas: supporting children who are dual language learners; promoting quality inclusion for children with disabilities; supporting young children who are racially and ethnically diverse; and engaging with, building respectful partnerships with, and communicating effectively with families. Josephina and her colleagues are pleased to see that their values and areas for enhancement coincide with NAEYC’S equity, DAP, and professional standards position statements and the joint statement on inclusion.

Josephina and her colleagues were now ready to take a closer look at their course syllabi to determine if coursework reflects their values and reflects what they want their students to know and be able to do when they complete the course. For example, does the course description include these values? What about course readings and assignments? Most significantly, what about the learning opportunities and assignments?

Measure What You Treasure: A Syllabus Rubric

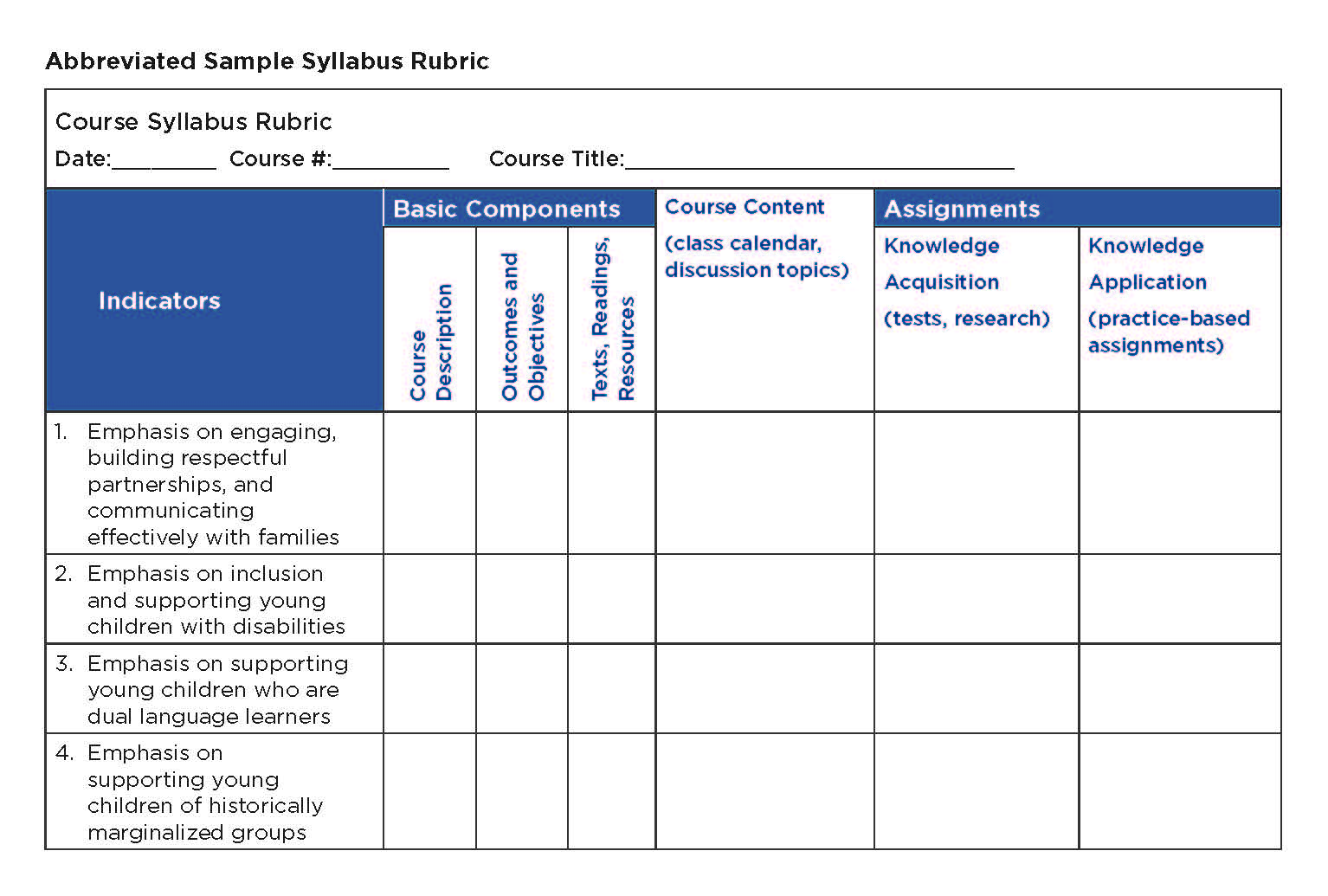

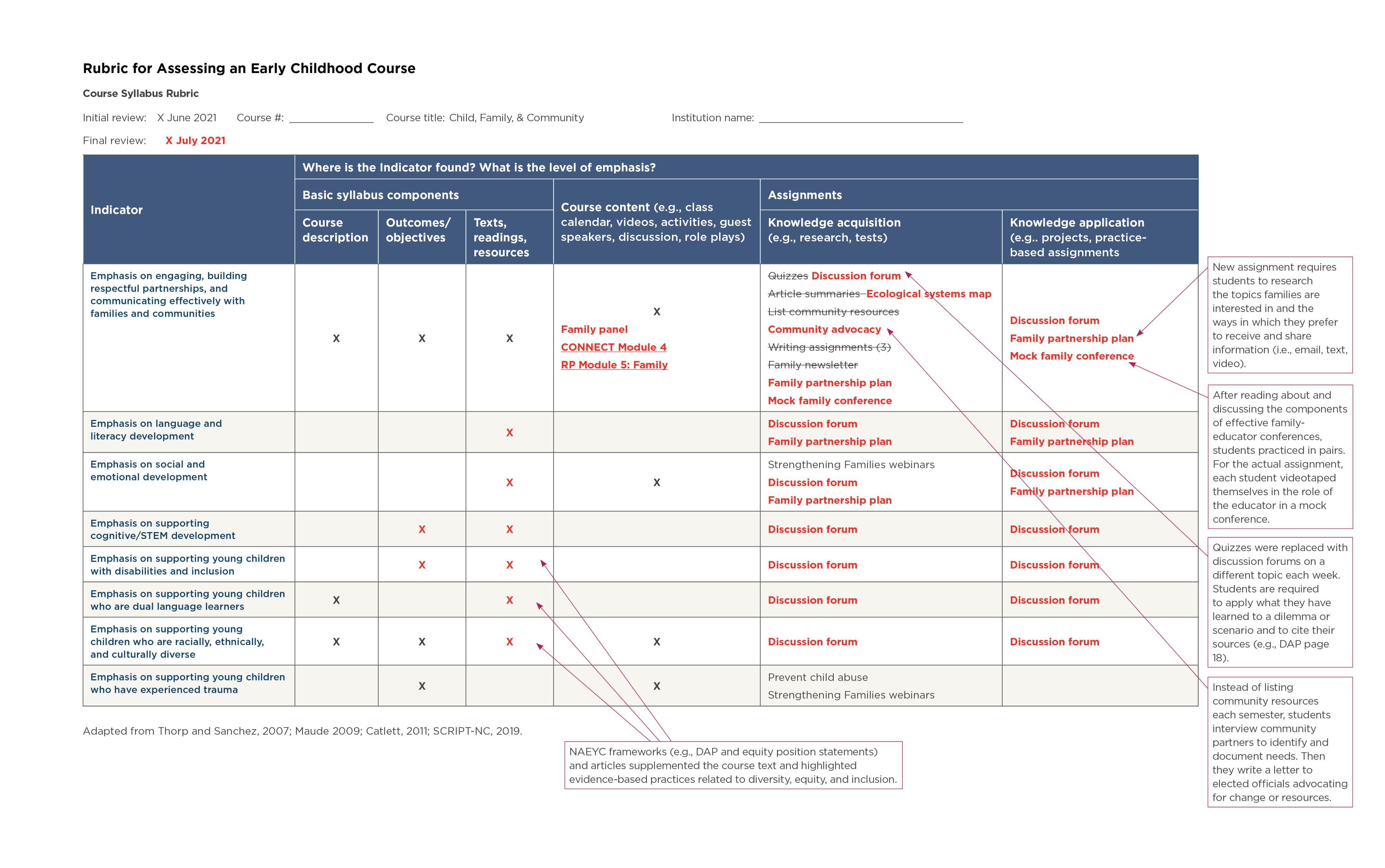

One practical strategy for examining the depth and breadth of course content is to use a syllabus rubric, which can help faculty and programs measure and appreciate what is present in a syllabus and adjust what is not. The indicators of a syllabus rubric may be drawn from a number of key sources. These include state and/or national frameworks with which courses should align, new insights like those provided by the Graduate of the Future activity, or even state or local priorities.

Using a syllabus rubric involves visually and electronically searching the components of the syllabus, including the physical copy provided to students, the course calendar, the main topics of study, and major assignments’ directions and rubrics, to find and evaluate these documents in relation to identified indicators. In addition to determining whether a course explicitly emphasizes key content and competencies, a syllabus rubric can help faculty to consider how content is incorporated. For example, professional development in the early childhood field should incorporate both “the acquisition of professional knowledge, skills, and dispositions as well as the application of this knowledge in practice” (NPDCI 2008, 3). This definition mirrors the current emphasis in NAEYC’s professional standards and competencies, which draws attention to the importance of what early childhood educators know and can do by focusing on both knowledge acquisition and knowledge application. (An abbreviated sample rubric is included below.)

In practice, each person uses the rubric to intentionally review the key components of the syllabus and to fill in the syllabus rubric. This snapshot documents the extent to which the indicators are addressed in that course. For example, for a specific course, is the emphasis on including children with disabilities mentioned exclusively in the student learning outcomes? Or is it only addressed in the course calendar? Is the emphasis on anti-bias practices addressed in an assignment that requires reading and summarizing articles (knowledge acquisition)? Or does a major assignment also require students to apply what they have read in a practice-based assignment? The rubric may also be used in a pre/post fashion to document changes in a syllabus. Rubrics can also be used to compare courses within the program. For example, if a program is pursuing NAEYC accreditation or reaccreditation, rubrics can be used to capture course-specific information and make it easy to see which standards, key elements, and supportive skills are emphasized across all courses.

Josephina decides to measure her program’s values and vision, starting with the department’s Child, Family, and Community course, as it is taken by all students and lays the foundation for all future coursework. To ensure the integrity of the snapshot captured by the syllabus rubric for this course, Josephina asks faculty colleagues to fill out a rubric she constructed from state and national standards and competencies and areas emphasized in the Graduate of the Future. Josephina’s colleagues assess whether and how the syllabus for the course addresses rubric indicators.

Josephina and her colleagues discover that while there is some emphasis on practices for including children with disabilities and using culturally responsive practices, the assignments mostly focus on knowledge acquisition (i.e., quizzes and discussing articles on how to support families who are racially, culturally, and linguistically diverse). Josephina resolves to make the shift to emphasizing practices that will support knowledge application. For example, Josephina and the course instructor decide to assign role playing, providing various scenarios of possible conversations with families, children, and other educators, so that candidates can put into action the evidence-based practices they have taken from the articles. Submitting videos of virtual role plays of these conversations not only encourages the students to apply these practices but also helps faculty members to give feedback.

As demonstrated in the vignette, the snapshot provided by a completed syllabus rubric can assist faculty in seeing where and how to incorporate more explicit emphasis on valued indicators in each course and include activities that address both knowledge acquisition and knowledge application.

Check for Alignment, Depth, and Explicitness: Syllabus Deconstruction and Reconstruction

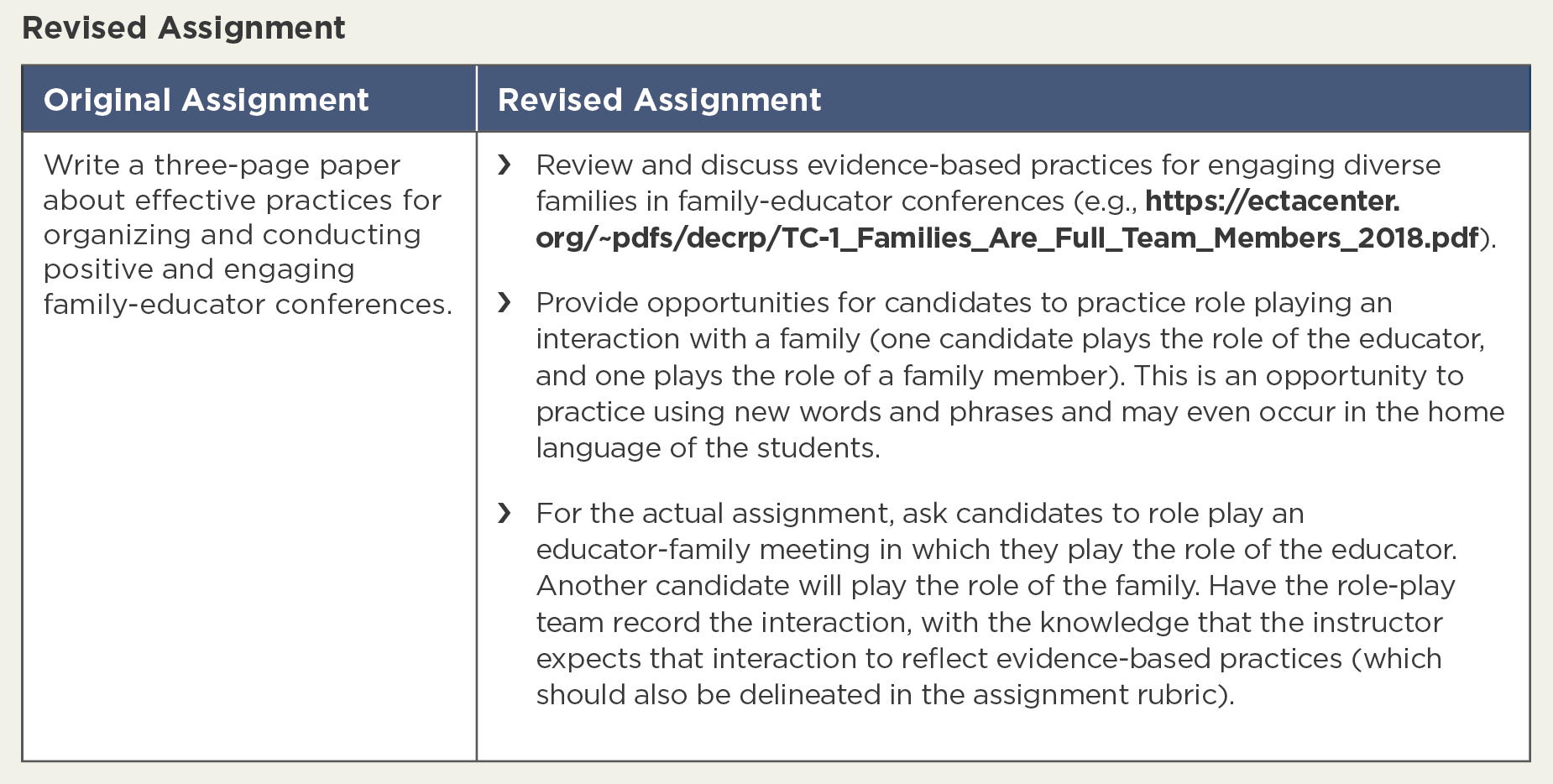

The final strategy entails incorporating new and explicit content and practices through deconstruction and reconstruction. Syllabus deconstruction refers to the process of examining each course component for alignment with rubric indicators, while reconstruction occurs when new methods, resources, and requirements that reflect the program’s values are added to the course. Importantly, reconstruction that brings about measurable shifts in the preparation of equitable and inclusive early childhood educators is unlikely to be achieved through superficial adjustments, such as asking candidates to read a new article.

Many syllabi are absolutely packed with relevant content, activities, and assignments and would not necessarily be enhanced by increasing quantity alone. Assignments are key to the deconstruction and reconstruction process. By incorporating assignments that require both knowledge acquisition and knowledge application, faculty can build what students know (through readings, discussion, activities, reflection, writing, and research) and determine what students are able to do (through practice-based assignments).

The Assignment Alignment tool, which was created as part of the Blueprint process, can support faculty to assess and adjust the breadth, depth, and explicitness of the assignments in a course. (See a sample of this tool at https://scriptnc.fpg.unc.edu/script-nc-assignment-alignment.) By entering the assignments for a course on an Assignment Alignment tool, a faculty member can evaluate their course assignments in a way that will answer three questions:

- Which of the course objectives/learning outcomes does this assignment address?

- Which of the course assignments requires knowledge acquisition? Knowledge application? Or both?

- Which of the course assignments explicitly focuses on areas of desired emphasis addressed by the indicators on the rubric, such as equity, inclusion, and cultural and linguistic responsiveness?

The beauty of this simple tool is that it can be adapted to very different campus and community contexts. For example, a program serving a community with a significant number of Black children and families added race, racism, anti-Blackness, and pro-Black pedagogy as areas of specific emphasis to be addressed in each course. Therefore, a revised Assignment Alignment tool helped to measure achievement of that goal in each course. Columns may also be added to the right to consider how the assignments of a specific course align with state and/or national frameworks.

By using the Assignment Alignment tool to review her syllabus, Josephina discovers that the assignments align well with some of the learning outcomes for the course. She also is able to discern which of the outcomes is being addressed superficially and to adjust the readings, calendar, and assignments to ensure that students are prepared to demonstrate the skills, knowledge, and dispositions needed to support children who are dual language learners, promote inclusion for children with disabilities, and utilize culturally responsive and equitable practices.

Resources to Support Course Deconstruction and Reconstruction

The course deconstruction and reconstruction process may require faculty to find and use new resources to further their own knowledge base and to shift content and assignments. Here are some suggestions for what to look for and where to find new resources to support targeted changes.

Look for Resources that Showcase the Intersection of the DAP Core Considerations

The DAP position statement underscores the necessity of early childhood educators having the knowledge and understanding to integrate “three core considerations: commonality in children’s development and learning, individuality reflecting each child’s unique characteristics and experiences, and the context in which development and learning occur” (NAEYC 2020, 6). Turning to scholarly and practitioner journals, books, and online resources can help delve into each core consideration and how they intersect in practice. For example, “Culturally Responsive Strategies to Support Young Children with Challenging Behavior,” by Price and Steed (2016), outlines practices that support positive teacher-child relationships, that help teachers learn about individual children and families, and that understand and appreciate the unique contextual factors that influence development.

Another example is the Pyramid Model Equity Coaching Guide by Ferro and colleagues (2020), which explains the connection between the pyramid model and equity practices. Faculty and staff may seek such resources for their own professional development or for the students they teach and mentor.

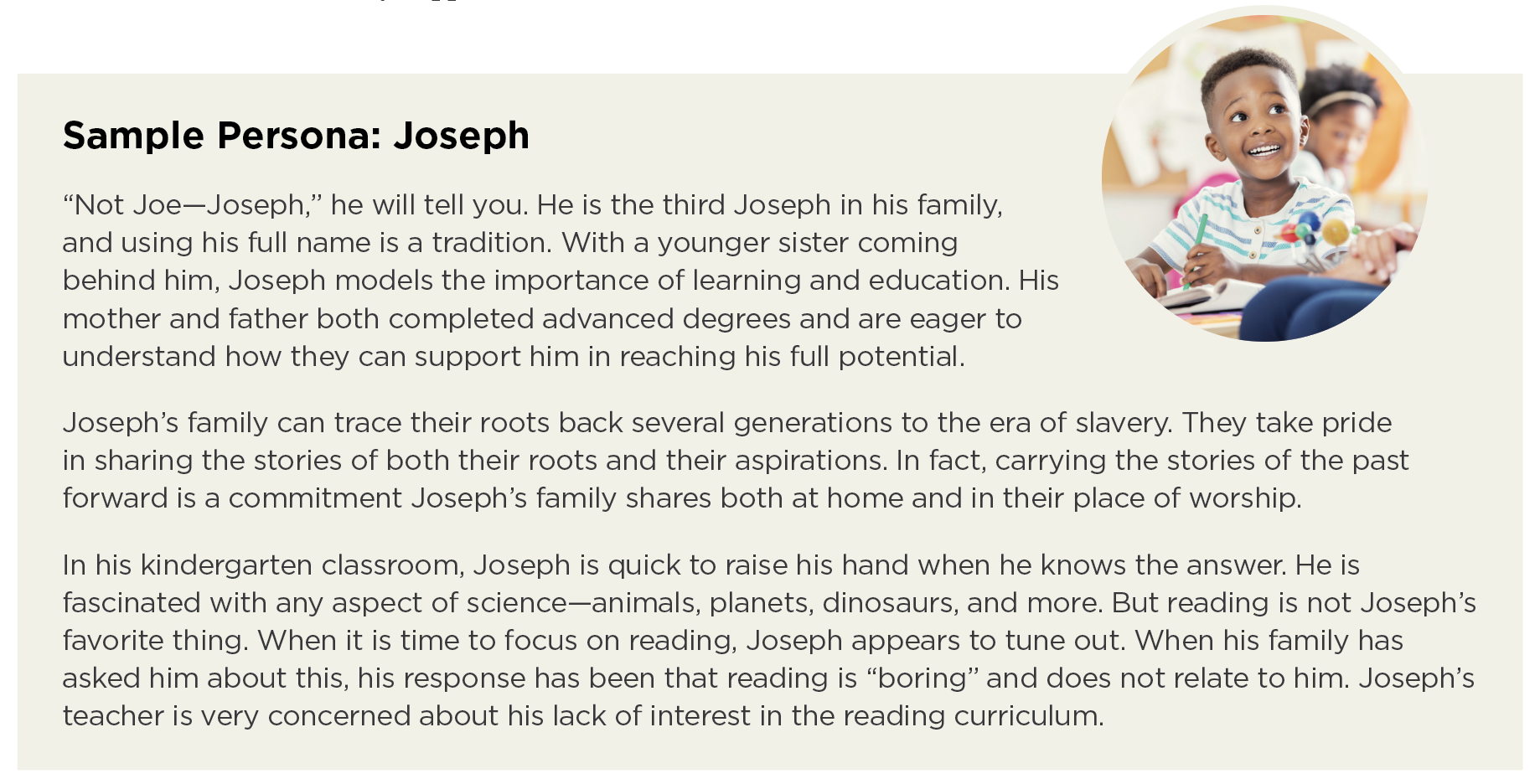

Consider Using Personas

Personas are a new tool for preparing future early childhood educators to develop a repertoire of evidence-based practices for supporting each and every child and family. Unlike more traditional vignettes or case studies, personas are concise stories of a child and family, each of which addresses the three core considerations of developmentally appropriate practice (commonality, context, and individuality). Each persona may be used in multiple ways to help teacher candidates individualize practices in ways that are humane and effective as they support students to view children and families from multiple vantage points. (See “Sample Persona: Joseph” for an example).

Use the Principles of Universal Design for Learning with Children and Adult Learners

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is based on the premise that providing learners with multiple ways to access course content and demonstrate what they know give each of them an equal opportunity to succeed. Just as the DAP position statement advocates to support each and every child and family, UDL and the deconstruction/reconstruction process encourage faculty to use their understanding of their adult students to make adjustments to content, depth, and breadth, while providing new opportunities for students to show what they know and can do.

For example, when reflecting upon her community context, Josephina recognized that some of the students in her class are English language learners. In the past, those students have shared that they are often insecure about talking with families or other early childhood colleagues in English. Using the principles of UDL, Josephina revised her major assignment for her course to provide opportunities for students to learn about and practice the skills she will be assessing. (See the table below for more information on how Josephina revised the assignment.)

Repurpose Available Guidance for Course Activities and Assignments

Position statements and other state and national guidance or frameworks can be featured in course activities and assignments in ways that build the capacity to provide equitable and inclusive practices. For example, the NAEYC position statement on advancing equity has a set of recommendations for early childhood educators. These recommendations can be repurposed to create a reflection tool for teacher candidates. For example, as part of a curriculum course, candidates might reflect on their knowledge of practices to implement each recommendation at the beginning of the semester and then again at the end of the semester. In contrast, they could instead identify an area in which they feel less confident and construct an independent study to build competence in that area.

Other resources that may be easily repurposed to support children with or at risk for disabilities are the practice improvement tools for implementing the Division for Early Childhood Recommended Practices (DEC 2014). For example, the organization’s website includes checklists that may be utilized when students watch a video to identify the practices that are and are not being used, both as part of planning for assignments and for self-reflection.

Discover Free, Searchable Collections of High-Quality Print, Audiovisual, and Online Materials

A number of early childhood-related websites have searchable databases of resources to help faculty prepare future educators in areas that include equity, inclusion, and culturally responsive teaching. For example, the Early Childhood Recommended Practice Module site, which emphasizes evidence-based practices for inclusion of young children with or at risk for delays and disabilities, has a free, searchable resource library. Other features of the site are activities, assignments, videos, and other resources for addressing seven areas of practice. In the SCRIPT-NC (Supporting Change and Reform in Preservice Teaching in North Carolina) database, faculty can search for resources by type of diversity (children with disabilities, children who are dual language learners), by type of resource (print, video), or both. SCRIPT-NC also has collections of free, annotated resources that emphasize diversity and equity that are organized by commonly taught course content like child guidance. (For links and additional descriptions, see the “Further Resources” at the end of this article.)

Access Resources that Support Assignment Makeovers

Faculty members who are interested in revising assignments to feature greater emphasis on knowledge application may want to consider the archived webinar resources on the SCRIPT-NC website. In addition to archived webinars on assignment makeovers, each of which has a PowerPoint presentation, handouts, and a recording to showcase multiple examples, there are resources related to effective online instruction, practice-based assignments, and evidence-based approaches for addressing commonly taught content. (“Rubric for Assessing an Early Childhood Course” below offers an example of what Josephina’s pre/post syllabus rubric looks like.)

Josephina and her colleagues resolve to use the syllabus rubric and Assignment Alignment tool to examine every course in their program. Then, using additional suggestions for implementation from the Blueprint process, they will look at how cohesive the sequences of knowledge acquisition and knowledge application are for students in individual courses and across the program and make adjustments accordingly. Finally, they schedule an update meeting with their community partners to share progress and get input on additional considerations.

Further Resources

See the following resources for more details on the information expressed in this article.

From NAEYC

The NAEYC website has free and extensive faculty resources to accompany the fourth edition of Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP).

- Appendix C: Changes to the Position, Changes to the Book: Resources and Strategies for Faculty offers ideas for how faculty members can easily incorporate an emphasis on DAP in their courses and field experiences.

- Charts are collections of tools for incorporating an emphasis on DAP in higher education programs. Each chart aligns with the content of an NAEYC standard (e.g., Child Learning and Development in Context) and includes reflection questions, activities, assignments, and additional resources for faculty.

Complete a brief form at https://www.naeyc.org/resources/developmentally-appropriate-practice/get-faculty-resources to access all the above-listed resources.

From the Blueprint

Additional information about the Blueprint process components is available to extend the examples in this article. Learn more about the Graduate of the Future process, tools and strategies for deconstructing and reconstructing courses, and examples of how other programs have used the process are available at https://fpg.unc.edu/publications/blueprint-process-enhancing-early-childhood-preservice-programs-and-courses. The publication also emphasizes the importance of looking across the findings for individual courses to build cohesion and continuity among the components of a higher education program (Phase 3).

From Supporting Change and Reform in Preservice Teaching in North Carolina (SCRIPT-NC)

Rich resources to support early childhood education faculty are available at the website of this project supported by the US Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs.

- Rubrics and how to use them are among the resources at https://scriptnc.fpg.unc.edu/tools-enhancing-program-quality. This is also the place to find collections of free infant/toddler, preschool, and early elementary personas.

- Course-specific resources organized by commonly taught early childhood course topics are at https://scriptnc.fpg.unc.edu/resources .

- Webinar recordings, PowerPoints, and handouts for early childhood faculty (e.g., Using Children's Books to Support Identity, Equity, and Inclusion) are archived at https://scriptnc.fpg.unc.edu/faculty-webinars . SCRIPT-NC does at least four free faculty webinars each year.

- A searchable database of resources for faculty is at https://scriptnc.fpg.unc.edu/resource-search.

From the Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center (ECTA)

Based on the Division for Early Childhood (DEC) Recommended Practices, the tools at this website can be used by faculty to prepare their students to support young children who have, or are at-risk for, developmental delays or disabilities and their families. The tools include performance checklists to help improve their skills, plan interventions, and self-evaluate. The site also has practice guides to explain evidence-based practices and how to do them using videos and vignettes. Each tool is available in both English and Spanish at https://ectacenter.org/decrp/ . Free online modules have also been developed to support faculty in teaching about the Recommended Practices and are available at https://rpm.fpg.unc.edu/ .

Photographs: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, et al. 2020. Unifying Framework for the Early Childhood Education Profession. Washington, DC: NAEYC. http://powertotheprofession.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Power-to-Profession-Framework-03312020-web.pdf

Catlett, C., S.P. Maude, & M. Skinner. 2016. “The Blueprint Process for Enhancing Early Childhood Preservice Programs and Courses.” Unpublished manuscript. Retrieved online at https://fpg.unc.edu/publications/blueprint-process-enhancing-early-childhood-preservice-programs-and-courses

Catlett, C., S.P. Maude, M. Nollsch, & S. Simon. 2014. “From All to Each and Every: Preparing Early Childhood Professionals to Support Children of Diverse Abilities” in Young Exceptional Children Monograph Series No. 16: Blending Practices for All Children (111–124). K. Pretti-Frontczak, J. Grisham-Brown, & L. Sullivan, eds. Los Angeles: Division for Early Childhood.

DEC (Division for Early Childhood). 2014. DEC Recommended Practices in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education 2014. Report. https://d4ab05f7-6074-4ec9-998a-232c5d918236.filesusr.com/ugd/95f212_12c3bc4467b5415aa2e76e9fded1ab30.pdf

DEC/NAEYC. 2009. “Early Childhood Inclusion: A Joint Position Statement of the Division for Early Childhood (DEC) and the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC).” Joint position statement. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/inclusion%20statement.pdf

Ferro, J., L. Fox, D. Binder, & M. von der Embse. 2020. Pyramid Model Equity Coaching Guide. Guide. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida. https://challengingbehavior.cbcs.usf.edu/docs/Equity-Coaching-Guide.pdf

Goffin, S.G. 2015. Professionalizing Early Childhood Education as a Field of Practice: A Guide to the Next Era. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

IMNRC (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council). 2015. Transforming the Workforce For Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Maude, S.P., C. Catlett, S. Moore, S.Y. Sánchez, E. Thorp, & R. Corso. 2010. “Infusing Diversity Constructs in Preservice Teacher Preparation: The Impact of a Systematic Faculty Development Strategy.” Infants and Young Children 23 (2): 1–19.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2019a. “Professional Standards and Competencies for Early Childhood Educators.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/professional-standards-competencies

———. 2019b. “Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education: A Position Statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity

———. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice: A Position Statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/developmentally-appropriate-practice

NPDCI (National Professional Development Center on Inclusion). 2008. What Do We Mean by Professional Development in the Early Childhood Field? Report. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute, NPDCI. https://npdci.fpg.unc.edu/sites/npdci.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/NPDCI_ProfessionalDevelopmentInEC_03-04-08_0.pdf

Price, C.L., & E.A. Steed. 2016. “Culturally Responsive Strategies to Support Young Children with Challenging Behavior.” Young Children 71 (5): 36–43.

Sarah Garrity, EdD, is the interim senior associate dean and an associate professor in child and family development in the College of Education at San Diego State University. She was a practitioner in the field of early care and education for almost 20 years as a Head Start teacher and administrator, program director for a state-funded program, and literacy coach. [email protected]

Camille Catlett, is a consultant working in multiple states and institutions of higher education to incorporate explicit and intentional emphasis on culture, equity, and individual diversity in early childhood and early childhood special education coursework, field experiences, and program practices. [email protected]